|

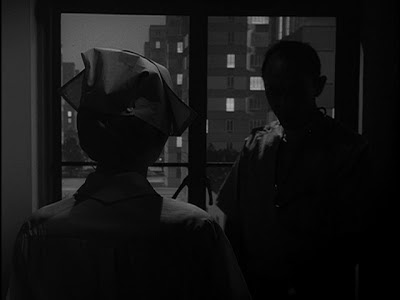

| Agnes Moorehead meets the Invaders |

“The Invaders”

Season Two, Episode 51

Original Air Date: January 27, 1961

Cast:

Woman: Agnes

Moorehead

Astronaut Voice: Douglas Heyes (uncredited)

Crew:

Writer:

Richard Matheson (original teleplay)

Director:

Douglas Heyes

Producer:

Buck Houghton

Associate Producer: Del Reisman

Production Manager: E. Darrell Hallenbeck

Director of Photography: George T. Clemens

Art Direction:

George W. Davis and Philip Barber

Set Decoration:

Henry Grace and H. Web Arrowsmith

Assistant Director: Lindsey Parsons, Jr.

Casting:

Ethel Winant

Editor: Leon

Barsha

Sound:

Franklin Milton and Charles Scheid

Music: Jerry

Goldsmith

And Now, Mr. Serling:

“Next week we bring you a show called ‘The Invaders’

written by Mr. Richard Matheson and in this room you’ll watch Ms. Agnes

Moorehead in a tension-riddled attempt at escape…from a pair of very improbable

housebreakers. This one we recommend to science fiction buffs, fantasy lovers,

or to anyone to grip the edge of his seat and take a twenty-four minute trip

into the realm of terror.”

Rod Serling’s Opening Narration:

“This is one of the out-of-the-way places. The

unvisited places. Bleak. Wasted. Dying. This

is a farmhouse, handmade, crude. A house without electricity or gas. A house

untouched by progress. This is the woman who lives in the house, a woman who’s

been alone for many years. A strong, simple woman whose only problem up until

this moment has been that of acquiring enough food to eat. A woman about to

face terror which is even now coming at her from the Twilight Zone.”

Summary:

An

old woman lives alone in a ramshackle house on a barren stretch of land few

would willingly choose to call home. While washing the dishes one evening, she

hears a loud, piercing noise followed immediately by a crash. After a few

moments she climbs up to the attic to investigate. Upon entering the attic she

discovers that a small air vessel of some kind has crashed through her roof. The

vessel is round and thin with a diameter of about three feet. The woman

approaches the vessel with caution. As she does so a small drop-door begins to

descend from underneath the ship and a tiny figure emerges. The figure is fully

clothed and his face cannot be seen. Frightened, she kicks the figure through

the attic opening down into the bottom interior of the house and swiftly shuts

the door. She notices a second figure standing on the opposite end of the room.

The figure aims his arm at the woman and fires something at her. She is too big

for the tiny weapon to do any significant harm but its effects are still

painful and she fleas back to the kitchen.

After

she dresses her wounds she begins to look for figure number one. She notices that one of her kitchen knives is

missing. She searches the house in extreme caution. One of the figures emerges

from under a floorboard and plunges the knife into her foot. She screams in

pain. She runs to the kitchen and grabs a hatchet. After having her hand sliced

open while grabbing the makeshift door handle on her bedroom door she enters

into her bedroom and finds one of the tiny figures hiding under a blanket. She

approaches the blanket slowly and grabs the moving mass underneath. She is then

confronted by the second figure shooting at her from the ledge of a nearby

window. She shoves the figure through the window sending it to the ground

below. She wraps the other figure up in the blanket and slams it down on a

table repeatedly as if she were trying to bust the table open with a

sledgehammer. She stops once the figure goes limp.

She

hears noise above her. She climbs up to the attic and approaches the ship, her

fingers gripped around the handle of the hatchet.

She

hears a voice.

“Gresham

is dead,” the voice says. “Incredible

race of giants here. No counter attack,

too powerful! Stay away! Gresham and I are…finished.”

The

woman begins to smash the ship in a violent frenzy until she collapses from

exhaustion. Afterwards, we see the only part of the ship left intake. Printed

in English in large block letters are the words: U.S. Air Force: Space Probe

No. 1.

Rod Serling’s Closing Narration

“These are the invaders: the tiny beings from the tiny

place called Earth, who would take the giant step across the sky to the

question marks that sparkle and beckon from the vastness of the universe only

to be imagined. The invaders, who found

out that a one-way ticket to the stars beyond has the ultimate price tag. And we have just seen it entered into a

ledger that covers all the transactions of the universe, a bill stamped ‘paid

in full,’ and to be found on file…in the Twilight Zone.”

Commentary:

Never

a program to shy away from a challenge, the second season of The Twilight Zone had already given

audiences Rod Serling’s “Eye of the Beholder,” an episode in which none of the

characters’ faces can be seen until the end of the story. Now the show offered

viewers a story with only one performer who doesn’t utter a single line of dialogue

for the entire twenty-three minutes that she is on screen. Her thoughts and

emotions are conveyed through facial expressions and the use of pantomime,

making it one of the most memorable episodes in the entire Twilight Zone canon.

Never

a program to shy away from a challenge, the second season of The Twilight Zone had already given

audiences Rod Serling’s “Eye of the Beholder,” an episode in which none of the

characters’ faces can be seen until the end of the story. Now the show offered

viewers a story with only one performer who doesn’t utter a single line of dialogue

for the entire twenty-three minutes that she is on screen. Her thoughts and

emotions are conveyed through facial expressions and the use of pantomime,

making it one of the most memorable episodes in the entire Twilight Zone canon.

For

an episode that has scant dialogue and is shot in real time, “The Invaders” feels

surprisingly fast-paced, with tension instilling itself during the first

moments of the episode and not letting up until its denouement. This is one of

only a handful of episodes that breaks the formula of the opening sequence

which usually consisted of a teaser followed by Serling’s appearance on screen.

Here, the audience is given no information before Serling’s introductory

monologue. Instead, Matheson and Serling

grab the viewer’s attention as soon as the title sequence is over with Serling

launching into what may be the single most effective opening line in any

episode of the show:

“This is one of the out-of-the-way places. The unvisited places. Bleak.

Wasted. Dying.”

The

rest of the monologue continues in a similar manner with Serling describing

both the woman and the house in an unflattering fashion. When Matheson first

began writing for the show he didn’t attach an introductory or closing

monologue to any of his scripts believing that Serling preferred to write the

monologues himself. But he found out later that this was not the case and began

to write them himself. It can be assumed that by this point Matheson had begun

scripting his own monologues, for this example in particular resembles

Matheson's prose style even though it was written specifically to be spoken by

Rod Serling. Its effectiveness lies in not only what is being described but the

way in which the words are strung together. Its terse delivery and harsh language

immediately grab the viewer’s attention and gives them a glimpse into the world

of this character.

Matheson had explored the theme of

role reversal between human beings and extraterrestrial life a decade earlier

in his short story “Third from the Sun,” which was adapted by Rod Serling

during season one. In this story the audience is led to believe they are

watching a family escape from an Earth on the brink of a nuclear apocalypse

only to find out by the end of the story that it is an alien family traveling

to Earth. He would also recycle the premise and basic plot structure of

"The Invaders" for his short story “Prey,” which was published in the

April, 1969 issue of Playboy. “Prey”

tells the story of a young woman alone in her apartment with a Zuni fetish doll

that she has purchased for her boyfriend. After only a few paragraphs, the Zuni

doll comes to life after the woman accidentally removes a restricting charm

from around the doll's neck. The doll proceeds to stalk the woman around her

tiny apartment for the remainder of the story trying to kill her. When

interviewed, Matheson said that his original pitch for “The Invaders,” a script

titled "Devil Doll," was much closer to the plot of "Prey"

but that producer Buck Houghton and series creator Rod Serling thought it was

too grim a tale and suggested that he set it on another planet and try to tone

down the violence. “Prey” was later made into a segment of the

made-for-television horror anthology film Trilogy

of Terror (ABC, 1975). This film was intended as the pilot episode for a

possible anthology series but was never picked up by a network. Trilogy of Terror was directed by Dark Shadows creator Dan Curtis based on

three of Matheson's short stories, "The Likeness of Julie,"

"Needle in the Heart," (or "Therese") and

"Prey." All three segments

feature Karen Black in the lead role.

The first two segments were adapted by writer William F. Nolan, a close friend

of Matheson's and frequent collaborator with Dan Curtis, but the “Prey”

segment, titled “Amelia” in the film, was adapted by Matheson, the writer

perhaps sensing something special about the segment as it is undoubtedly the

most fondly remembered portion of the film. Curtis directed a sequel to the

film, Trilogy of Terror II, in 1996 which

includes a sequel to the “Amelia” segment from the first film, picking up right

where the original segment ended. William F. Nolan wrote the screenplay for

this segment.

Calling the shots on “The Invaders” was director Douglas Heyes who had become the show’s good luck

charm when it came to technically challenging episodes such as this one. Unfortunately,

this would be the last episode directed by Heyes. The Twilight Zone never staffed regular directors, writers, or

actors. Everything was freelance, with the producers purchasing the stories

they felt were right for the show and hiring the people they felt were right

for that particular story. Heyes made nine episodes during the first and second

seasons of the show, although his influence can be felt throughout the entire

run of the series. He had an eclectic style that lent itself to the show

remarkably well. If Houghton knew that an episode was going to be challenging

Heyes was usually his first choice.

Heyes’s

second major contribution to the horror/fantasy genre is his work on Boris Karloff’s Thriller. Around the

same time that he made “The Invaders” Heyes had already begun working on

episodes of Thriller at NBC. Although

several different versions of the show’s history have been presented over the

years it is generally agreed upon that Heyes played a significant role in

helping it evolve from a bland imitation of Alfred

Hitchcock Presents to a program of rich gothic horror more in line with the

image of Boris Karloff. Heyes wrote and directed the first genuine horror

episode of the show, “The Purple Room,” for its first season. Later in the

season he directed the episode “The Hungry Glass” which he adapted from the

Robert Bloch story “The Hungry House.” Heyes’s third and final episode was “The

Premature Burial” which he directed and co-adapted with William D. Gordon from

the story by Edgar Allan Poe. Although he was only directly involved in three

episodes Heyes, along with many others most notably producer William Frye,

helped save the show from obscurity and made it a program that is still

enjoyed and discussed today.

After

his work on Thriller and The Twilight Zone, Heyes wrote three

segments of Night Gallery including

both segments of the debut episode “The Dead Man,” which he also directed, and

“The Housekeeper.” He also wrote the segment “Brenda” for the second season of

the show. He continued to publish novels. The

12th of Never was published by Random House in 1963 and The Kill was published by Ballantine

Books in 1985 and was nominated for a Shamus Award for Best Original Paperback.

Today he is probably best remembered for helming the sprawling historical

miniseries Captains and Kings (NBC,

1976)—which features an appearance by Richard Matheson as President James

Garfield—and North and South (ABC,

1985). Much of his writing appeared under the pseudonym Matthew Howard. He died

in 1993 at the age of 73.

In

an interview with Marc Scott Zicree, Heyes said that once he read the script

for “The Invaders” he knew that the set design had to be as simple as possible

to make the audience believe that they were watching a story set on Earth. Nothing

specific to Earth, nor anything overtly foreign, could be used as a set piece. This

is why the woman’s house looks so primitive. All of the set pieces seen inside

the house are the basic tools one would need for survival. Heyes also revealed

that the “invaders” were simply puppets that were manually operated by various

crew members. Heyes and the crew members wore black, long sleeve t-shirts and

were able to maneuver the puppets by placing their hand through an opening on

the back side of the puppet and moving the legs with their fingers. This is why

the spacemen move with such slow, wooden gestures. Over the years the tiny

invaders have been the subject of criticism and ridicule from fans because of

their primitive appearance. However, the story is so good and Moorehead’s

performance so captivating that this is quickly forgotten. Heyes said he based

the spacemen on the Michelin Tire Man. He also revealed that the voice of the

astronaut at the end of the episode was actually his voice.

Jerry

Goldsmith forgoes his usual soft dream-like style to deliver some of the most

memorable music from any episode of the show. No doubt taking a cue from

Bernard Hermann’s famous score for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which was released the year before, Goldsmith uses mostly

harsh strings and occasional piano arrangements which greatly add to the

unsettling atmosphere in this episode.

And finally, although Matheson

delivers a solid script and both Heyes and Goldsmith help breathe life into it,

this episode more or less belongs to Agnes Moorehead. A veteran character

actress of stage and screen, Moorehead was a well-known name by the time this

episode aired. In the 1930’s she became friends with Orson Welles and

eventually joined his Mercury Theatre Company.

In 1938 she took part in Welles’s famous radio adaptation of H. G.

Welles’s War of the Worlds. After

Welles moved to Hollywood she appeared in several of his films including Citizen Cane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). She

went on to have a wildly successful film career appearing alongside the likes

of Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Bette Davis, and Vincent Price. But it was

her role as Endora on Bewitched that

would immortalize her forever (much to her reported irritation).

Heyes

recruited Moorehead for this episode specifically based on her performance in a

one-woman radio adaptation of Lucille Fletcher’s “Sorry, Wrong Number” (1948)

for the show Suspense. He was

impressed by her ability to sustain terror for the entire half hour episode and

figured that she would be a good fit for “The Invaders.” The challenge here of

course is that she had no dialogue to help her move the plot along or develop

her character. As there is little dialogue in this episode most of the story is

told through the actions, mannerisms, and facial expressions of Moorehead’s

character. Years earlier she studied under renowned pantomime artist Marcel

Marceau and her performance here is one of the best the show ever offered. It is

crude and even embarrassing at times but she still manages to be completely

compelling. Her mannerisms are almost primitive and there is one scene where

the woman, exhausted, is seen drooling uncontrollably. It is as authentic as

any performance that one is likely to see on television from this or any other

era.

Although

“The Invaders” has come to be a fan favorite and one of the more recognizable

episodes of the show it should be noted that Richard Matheson was not a fan of

it, although he did praise Moorehead’s performance. He was irritated by the

stilted movements and absurd mannerisms of the tiny invaders. He also thought

the episode moved much slower than his original script. Even so the idea was

unique enough to cement this story in the cosmos of popular culture and make his miniature space invaders immortal.

Grade: A

Grateful acknowledgement to:

“Douglas Heyes: Behind the

Scenes at The Twilight Zone”

interview with Heyes conducted by Ben Herndon. Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone Magazine (August, 1982) edited by

T.E.D. Klein

This is a Thriller by Alan Warren (McFarland and Company, 1996)

The Twilight Zone Companion, second edition by Marc Scott Zicree (Silman-James Press, 1992)

Notes:

|

| Original design sketch by director Douglas Heyes featured in an interview with Heyes in the Aug, 1982 issue of Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine |

--Agnes Moorehead also appeared in two episodes of Rod Serling's Night Gallery, "Certain Shadows on the Wall," scripted by Serling from a

story by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, and "Witches' Feast."

--Douglas Heyes directed nine episodes of The Twilight Zone and

was considered by producer Buck Houghton to be the go-to director for

technically challenging episodes. “The Chaser,” “The After Hours,” “The Howling

Man” and "Eye of the Beholder" are among his contributions to the

show. Heyes wrote both segments of the first episode of Rod Serling's Night Gallery, "The Dead Man" (based on the story by Fritz Leiber) which he also directed and "The Housekeeper" which he wrote under the pseudonym Matthew Howard. He also wrote the season two segment "Brenda" (based on the

story by Margaret St. Clair) under this pseudonym.

--"The Invaders" was adapted into a Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring Kathy Garver.

--Brian