Recently, we were fortunate enough to

correspond with legendary author William F. Nolan. Nolan was a core member of

the Southern California School of Writers in the 1950s and 1960s, having

collaborated on numerous occasions with his close friends and Twilight Zone writers Ray Bradbury,

Charles Beaumont, Richard Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, and John Tomerlin.

Nolan is the author of the 1967

dystopian novel Logan’s Run (written

with George Clayton Johnson), which

has been adapted into a film, a television series, multiple comic books series,

and followed by two Nolan-penned sequels, Logan’s

World (1977) and Logan’s Search (1980).

He is the author of a highly regarded body of short fiction, primarily in the

horror, fantasy, science fiction, and suspense genres, which have been

collected across several volumes including Impact-20

(1963), Alien Horizons (1974), Things Beyond Midnight (1984), Night Shapes (1995), Dark Universe (2001), and Like a Dead Man Walking (2014). His

novels include The Black Mask series,

the Sam Space series and the horror

novel Helltracks (1991), among many others.

Nolan is the author of the 1967

dystopian novel Logan’s Run (written

with George Clayton Johnson), which

has been adapted into a film, a television series, multiple comic books series,

and followed by two Nolan-penned sequels, Logan’s

World (1977) and Logan’s Search (1980).

He is the author of a highly regarded body of short fiction, primarily in the

horror, fantasy, science fiction, and suspense genres, which have been

collected across several volumes including Impact-20

(1963), Alien Horizons (1974), Things Beyond Midnight (1984), Night Shapes (1995), Dark Universe (2001), and Like a Dead Man Walking (2014). His

novels include The Black Mask series,

the Sam Space series and the horror

novel Helltracks (1991), among many others.

Nolan’s work in film and television is

showcased in his collaborations with director Dan Curtis, which includes

screenplays for The Turn of the Screw (1974),

Trilogy of Terror (1975), Burnt Offerings (1976), and Trilogy of Terror II (1996).

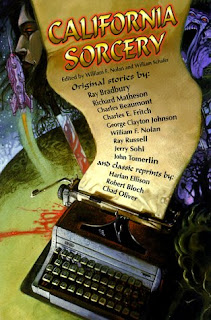

Nolan is also an accomplished editor,

having compiled such anthologies as The

Pseudo-People (1965), Man Against

Tomorrow (1965), A Wilderness of

Stars (1969), A Sea of Space (1970),

and, with Martin H. Greenberg, Urban

Horrors (1990) and The Bradbury

Chronicles: Stories in Honor of Ray Bradbury (1991). With William Schafer,

Nolan compiled the essential Group anthology, California Sorcery (1999). In recent years, Nolan has worked

closely with author, editor, and filmmaker Jason V. Brock on such projects as William F. Nolan: A Miscellany (2011), The Bleeding Edge: Dark Barriers, Dark

Frontiers (2009), The Devil’s

Coattails: More Dispatches from the Dark Frontier (2011), and the comic

book series Tales from William F. Nolan’s

Dark Universe.

Nolan’s work in non-fiction fields is

equally accomplished and includes such essential volumes as The Ray Bradbury Companion (1975), The Work of Charles Beaumont: An Annotated

Bibliography & Guide (1986; 2nd ed. 1990), and Nolan on Bradbury (2013). He has written essays on such science

fiction luminaries as Theodore Sturgeon, Alfred Bester, Chad Oliver, and Philip

K. Dick, as well as book-length biographies of Dashiell Hammett, Steve McQueen,

and John Huston, among others. He is the author of two books on writing, How to Write Horror Fiction (1990) and Let’s Get Creative: Writing Fiction That

Sells (2006).

Nolan’s work in non-fiction fields is

equally accomplished and includes such essential volumes as The Ray Bradbury Companion (1975), The Work of Charles Beaumont: An Annotated

Bibliography & Guide (1986; 2nd ed. 1990), and Nolan on Bradbury (2013). He has written essays on such science

fiction luminaries as Theodore Sturgeon, Alfred Bester, Chad Oliver, and Philip

K. Dick, as well as book-length biographies of Dashiell Hammett, Steve McQueen,

and John Huston, among others. He is the author of two books on writing, How to Write Horror Fiction (1990) and Let’s Get Creative: Writing Fiction That

Sells (2006).

Nolan’s output also includes poetry,

art, articles, teleplays, and books on a variety of subjects. Of particular

interest are his two books on automobile racing compiled with Charles Beaumont,

The Omnibus of Speed (1958) and When Engines Roar (1964). Nolan has won

multiple Bram Stoker Awards from the Horror Writers Association, including a

Grand Master Award in 2014. He won the International Horror Guild’s Living

Legend Award in 2001 as well as the World Horror Society Grand Master Award in

2015. Nolan’s accolades also include awards from the Mystery Writers of

America, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, and the World

Fantasy Convention.

Mr. Nolan was kind enough to talk to us

about his time with the Group, his assessment of The Twilight Zone, and his long and successful writing career.

-JP

Vortex: You were a

core member of the creative group which produced so much of the material seen

on The Twilight Zone. What was the feeling amongst members of

that group during production of the series?

Nolan:

They were proud to be a part of what

they came to realize was a unique series. Everyone admired Rod Serling, but

none of us realized the impact that the show would have. We just thought it was

another TV series. At the time, they greatly appreciated having their scripts

shot exactly as written. Most shows would make significant changes, but most of

the Twilight Zone episodes were shot

pretty much as they were imagined by the writers.

Vortex: Can you talk about your Twilight Zone

story, “Dreamflight,” written with George Clayton Johnson? What was it about and why did it go unproduced?

Were there any other Twilight Zone

stories which you wrote but were never produced?

Nolan:

It was a modern version of Sleeping Beauty. In our take, an

airliner suddenly lost all four engines and was headed down for a fatal crash.

Then, at the last minute, a young man stepped up to a still sleeping girl and

kissed her goodbye. Instantly, all four engines roared back to life, and the

plane was saved. Saved by a magic kiss.

Rod liked it, paid us for it, and I’m

sure would have produced it. But by that time, Twilight Zone was headed into its next season with hour long

episodes. Written to a half-hour format, “Dreamflight” didn’t fit.

“Dreamflight” did get printed in the 2006 anthology, Forgotten Gems from the Twilight Zone, Volume 2. This was my one

and only teleplay for the series. Alas, I was too busy to write other episodes

for the show.

Vortex: One of

distinguishing characteristics of the Southern California Group of Writers was

the willingness to collaborate on a variety of creative projects, from novels

and anthologies, to television and film scripts. What fostered this desire to

work together? How did close friendship affect the creative process?

Nolan:

We in the Group were all close

friends: Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, Charles Beaumont, Chad Oliver, Richard

Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, John Tomerlin – all of us were close. We

enjoyed working with one another, as we felt we were getting a bonus in doing

this; that two sets of imagination added to every collaborative project. After

all, two heads are better than one. Logan’s

Run was better with Johnson’s contribution.

We also criticized each other’s work

relentlessly, sometimes spending all night at a coffee shop doing so. But it

made us each a stronger writer than we would have been alone.

Vortex: How would you

describe your style of writing?

Nolan:

It varies considerably. My Logan novels are swift and direct, never

a wasted word. Extremely fast-paced. Hard edged. I’ve used many styles over the

years with my work. Depending on the kind of story I’m telling. Plot and

character dictate how I write. To sum up: I have no primary writing style. This

way I stay fresh. My cardinal rule: never bore the reader. I do my best to

follow this rule.

Vortex: Your best

known work is the novel Logan’s Run but a large portion of your career has been

dedicated to the short story form, including much of your finest work. What

continues to draw you to the short story form and how has your approach to

short story writing changed over the course of your career?

Nolan:

The short story is, to my mind, the

purest form of fiction. They demand a tight structure, sharp dialogue, and a

clear beginning, middle, and end. They are direct, akin to a one round knockout

punch in a fifteen-round bout. With each new story, I attempt to “push the

envelope” – to do things I’ve never done before. I love writing them.

Vortex: You produced

an influential body of work for film and television, particularly your work

with producer/director Dan Curtis. Can you talk about how you broke into film

and television? What do you feel are your most successful forays into those

mediums?

Nolan:

Back in 1959, Charles Beaumont and

John Tomerlin both allowed me to co-write teleplays with them under their

by-line. That’s how I learned how to write for television. By 1971, I was able

to strike out on my own when I adapted my story “The Joy of Living” for Norman

Corwin’s Canadian television series, Norman

Corwin Presents. Among my most successful projects for television: The Norliss Tapes, The Turn of the Screw,

Trilogy of Terror – and for film Burnt

Offerings – all with my friend, the late Dan Curtis, who produced and

directed them. Dan was a very talented guy, and I was recommended to him by

another good friend, the late Richard Matheson.

Vortex: Another

interesting aspect of your career is the large body of essays, biographies,

catalogues, and bibliographies you’ve produced, much of it exploring the

careers of your contemporaries in science fiction and fantasy. Can you tell us

about this dedication to cataloguing and commenting upon the work of your

contemporaries?

Nolan:

I’ve always been very interested in

what my fellow writers do. I enjoy exploring their output in bibliographic

form. Very satisfying, and I feel of real value. Plus, it offers a nice break

from my fiction.

I guess I’ve always had a preoccupation

with list making. In the Group, they called me “the old indexer.” I felt it was

important to record people’s accomplishments, even when they didn’t think so

themselves at the time. Sometimes, when asked about when a certain story

appeared and where, even Richard Matheson would say, “Go ask Bill. He knows

more about my work than I do.” I’d always have the answer.

This interest also led me to create the Ray Bradbury Review, the first critical

treatment of Bradbury’s work. I went on to do other bibliographies and several

full biographies. I have even kept a month-by-month journal of my own life

since my birth in Kansas City. Right now, I am working on my memories as I push

90 years of age.

Vortex: One of the

writers to whom you dedicated your career retrospective, Dark Universe,

was Charles Beaumont. Beaumont’s work has been kept alive largely through his

association with The Twilight Zone

but also by a dedicated group of readers and by Beaumont’s close friends such

as Ray Bradbury and yourself. With his inclusion into the Penguin Classics line

of books, Beaumont’s work has reached new heights of accessibility and

respectability. How did Beaumont’s work strike you at the time it was being

written and what do you feel is the quality of the work which elicits such

devotion from its readers?

Nolan:

Charles Beaumont was indeed a fine

writer. One of the trailblazers. His work had a lyrical quality and always

dealt with humanistic concerns. He was a superb storyteller, and my dear pal.

In many ways, I owe my career to him. I speak about him at length, and so does

Bradbury, Matheson, Johnson, and others, in the documentary Charles Beaumont: The Life of Twilight

Zone’s Magic Man. Of everything out there, I think that film most closely

captures the essence of why Beaumont was an important figure in all our lives.

Vortex: Charles Beaumont’s excellent fourth season

episode “Miniature” related to your own life at that time. Could you tell us

the story behind that episode?

Nolan:

Well for one thing, the character was

shy around women and Chuck (which is what we called Beaumont) was well aware of

this. It was partly his way of ribbing me, but I also have always had a thing

for miniature figures and models. Maybe it’s because my eyesight – I am

near-sighted in one eye, and far-sighted in the other – prevents me from really

seeing large objects in 3D. But a small object that I can hold up in front of

my face can become a whole world to me. I

can see it in its totality and study it. It fascinates me. Chuck was one of the

only people who knew me well enough to pick up on this and used it in the

story.

Vortex: You recently won a Bram Stoker Award for your

book, Nolan on Bradbury: Sixty Years

of Writing about the Master of Science Fiction. Before that you created publications such as The Ray Bradbury

Review and The Ray Bradbury

Companion. Although Bradbury only saw one

teleplay produced on The Twilight Zone,

his influence can be felt in everything seen on the series. Can you tell us what

Bradbury’s work and friendship meant to you personally and to the Group as a

collective?

Nolan:

Well of course, Bradbury was the

master, the role model for us all. He had a tremendous influence on modern

literature around the world. To the Group, he was our mentor. To me, a deeply

valued friend as well. Bradbury was generous to all of us. He spent time with

us and helped us with our problems. Even when we interrupted his writing, he

was never angry or impatient. He gave his time and advice freely and he helped

all of us with our careers.

Vortex: I feel that The Twilight Zone was the purest

creative expression of the Southern California Group. What do you feel are the

qualities of the series which causes it to endure and renew itself with each

succeeding generation?

Nolan:

The

Twilight Zone told human stories, no

matter how fantastic the basic concept might be. It used fantasy and fable to

illumine human character. Rod Serling deserves much credit for the creation of

a truly memorable series.

Thank

you again to William F. Nolan and a special thanks to Sunni Brock.

Visit William F. Nolan’s official

website

View William F. Nolan’s listing on the

Internet Speculative Fiction Database

A William F. Nolan cover gallery:

It's great that you were able to interview Mr. Nolan. I enjoyed reading what he had to say and learned some new things about what he has done.

ReplyDeleteGlad you enjoyed it, Jack. It was great to be able to talk with him. He's had such an amazing and prolific career and he's been such a keen observer of the science fiction and fantasy fields for many years that unfortunately I was only able to show but a small sample of his knowledge and memory of experience.

Delete