We’ve

made it a third of the way through our issue-by-issue look at Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone Magazine. In this series we take a detailed look at

each issue. For our capsule history of the magazine, go here.

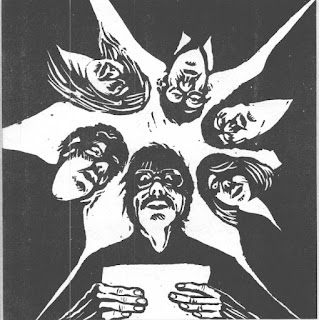

Cover art: Bruce Heapps

TZ

Publications, Inc.

President

& Chairman: S. Edward Orenstein

Secretary/Treasurer:

Sidney Z. Gellman

Executive

Vice-Presidents: Leon Garry, Eric

Protter

Executive

Publisher: S. Edward Orenstein

Publisher:

Leon Garry

Associate

Publisher and Consulting Editor: Carol

Serling

Editorial

Director: Eric Protter

Editor:

T.E.D. Klein

Managing

Editor: Jane Bayer

Assistant

Editor: Robert Sabat

Editorial

Assistant: Judy Linden

Contributing

Editors: Thomas M. Disch, Gahan

Wilson

Design

Director: Michael Monte

Art

Director: Wendy Mansfield

Art

Production: Susan Lindeman, Carol

Sun, Lori Hollander

Typesetting:

Irma Landazuri

Production

Director: Stephen J. Fallon

Controller:

Thomas Schiff

Ass’t

to the Publisher: Penny Layne

Public

Relations Mgr.: Jeffrey Nickora

Accounting

Mgr.: Chris Grossman

Accounting

Ass’t: Annmarie Pistilli

Office

Ass’t: Zuleyma Guevara

Circulation

Director: William D. Smith

Circulation

Mgr.: Carole A. Harley

Circulation

Ass’t: Katherine Lys

Northeastern

Cirulation Manager: Jacqueline Doyle

Eastern

Circ. Mgr.: Hank Rosen

West

Coast Circ. Mgr.: Gary Judy

Advertising

Manager: Rachel Britapaja

Adv.

Production Manager: Marina Despotakis

Advertising

Representatives: Barney O’Hara &

Associates

Contents:

--In the Twilight Zone: “Unmasking time

. . .” by T.E.D. Klein

--Other Dimensions: Screen by Gahan

Wilson

--Other Dimensions: Books by Thomas M.

Disch

--Other Dimensions: The ‘Heroes &

Heavies’ Quiz by Kathleen Murray

--Other Dimensions: War in Fantasyland

by Baird Searles

--Other Dimensions: Etc.

--The Evil Dead (review) by Stephen King

--John Carpenter: Doing His Own Thing

(interview) by James Verniere

--“Hell Is Murky” by John Alfred Taylor

--Required Reading: “Levitation” by

Joseph Payne Brennan

--“The Opening” by Bruce Boston

--TZ Screen Preview: Halloween III by James Verniere

--Country of the Dead by Randy Chisholm

(photos) & John Bensink (text)

--“Night Cry” by Katherine M. Turney

--“The Spook Man” by Al Sarrantonio

--“The Circle” by Lewis Shiner

--“Halloween Girl” by Robert Grant

--“The Screenplay” by Joseph Cromarty

--“The Smell of Cherries” by Jeffrey

Goddin

--Show-by-Show Guide: TV’s Twilight

Zone: Party Twenty by Marc Scott Zicree

--TZ Classic Teleplay: “A Quality of

Mercy” by Rod Serling

--Looking Ahead: In December’s TZ

--In

the Twilight Zone: “Unmasking time . . .” by T.E.D Klein

|

| T.E.D. Klein |

-Klein

gets straight to the contributor bios in this Halloween-themed issue. Among the

highlights: the return of Gahan Wilson as films reviewer, an essay on The Evil Dead by

Stephen King, an interview with John Carpenter, required reading from Joseph

Payne Brennan, Halloween stories by Al Sarrantonio, Lewis Shiner, and Robert

Grant, a preview of Halloween III, and

a feature on unusual epitaphs. The “Unmasking time” of the title refers to

Klein’s inclusion of photographs of some of the TZ Magazine staff. There are

photos of Klein, publisher Leon Garry, editorial director Eric Protter,

managing editor Jane Bayer, assistant editor Robert Sabat, art department

members Susan Lindeman, Lori Hollander, Michael Monte, Wendy Mansfield, Carol

Sun, and Irma Landazuri, production director Stephen J. Fallon, and advertising

production manager Marina Despotakis.

--Other

Dimensions: Screen by Gahan Wilson

|

| Poltergeist |

-Feeling

ambitious upon his return to the magazine, Wilson reviews three notable films: E.T.: The Extra Terrestrial (1982), The Thing (1982), and

Poltergeist (1982). Since E.T. and The Thing feature aliens as characters, Wilson expounds upon the pros and cons of

what he terms the “NHL,” or non-human lead, especially as it refers to E.T.

Wilson is enthusiastic in his review of

Steven Spielberg’s film, especially the performances of child actors Henry

Thomas and Drew Barrymore, the special effects from Carlo Rimbaldi, Spielberg’s

direction, and the script by Melissa Mathison, the writer who rewrote Richard

Matheson’s adaptation of George Clayton Johnson’s “Kick the Can” for Twilight

Zone: the Movie (1983). Wilson’s review of John Carpenter’s The

Thing (subject of the TZ Screen Preview

in the July, 1982 issue) is largely positive with particular praise for the

script from Bill Lancaster, Rob Bottin’s special makeup effects, and the

successful updating of the material. Wilson takes issue with the design of the

spaceship upon which the Thing arrives on Earth, feeling that it does not makes

sense for the amorphous physiology of the Thing to be able to pilot such a

vehicle. Fan theories have suggested that the Thing arrived as a stowaway on

the spacecraft, having attacked and absorbed the lifeform onboard. John

Carpenter, the director of The Thing, is

the interview subject in this issue. Finally, Wilson tackles the funhouse spook

film Poltergeist, directed by Tobe

Hooper and produced by Steven Spielberg. Wilson praises the cast but finds

fault with the film’s kitchen-sink approach, throwing everything at the viewer

while taking little time to explain anything. The film’s troubled production is

also briefly touched upon.

--Other

Dimensions: Books by Thomas M. Disch

-Disch

is in acerbic form in this review column as he cuttingly examines four novels.

Disch first takes his critical knife to Mickelsson’s

Ghosts by John Gardner. Disch writes:

“Gardner writes precisely the sort of over-earnest, symbol-laden tome that is

to the college writers’ workshop what the Model A was to Detroit. I can imagine

no one reading Mickelsson’s Ghosts with

pleasure except the more plodding students of Creative Writing, whose faith in

the eventual triumph of the patient imitation of approved models finds in

Gardner a kind of messiah.” Richard A. by

Sol Yurick fares little better under Disch’s critical eye. The prose style is

Disch’s primary point of contention and he offers an excerpt of purple prose as

example. His final judgment: “It’s only paper. Burn it.” Disch also suggests

burning John Shirley’s Cellars, a

horror novel currently gaining new and appreciative readers through a

resurgence of interest in paperback horror novels of the 1980s. Disch is not a

fan, however, and concludes this way: “So it goes, the grue alternating with

the hokum for 295 pages of prose that is eighty-five percent pulp padding and

fifteen percent amplified scream. There is, I will admit, an aesthetic to

screaming, and Shirley’s shriller screams can get to your crystal ware, but

screaming is, as a general rule, less effective on the printed page than in

rock music, where the silly lyrics are blessedly incomprehensible and the beat

goes on. Novels, alas, don’t have a rhythm section to keep them moving – so

when the pages refuse to turn: burn, baby, burn.” The final book under the

knife is Battlefield Earth by L. Ron

Hubbard. Disch characterizes the book as “to other, ordinary dumb books what a

Dyson sphere is to an ordinary lampshade – awesomely much bigger, though not

different in kind.” Disch criticizes the bits of autobiography that Hubbard

includes in the opening of the book, as well as the old-fashioned feel of the

novel. Disch admits, however, that the novel will almost certainly be a

critical and commercial success. A large advertisement for Battlefield

Earth is featured at the end of the

column. Disch included a portion of this review column, the section dealing

with Hubbard’s Battlefield Earth, in

his 2005 essay collection On SF.

--Other

Dimensions: The ‘Heroes & Heavies’ Quiz by Kathleen Murray

-The

quiz this month challenges the reader to match the hero or heroine of horror

movies with the bad guys who terrorize them. Below are the quiz and the answers

for those who wish to take the challenge.

Illustration by Jonathan Lewis

-Searles

(1934-1993) was the proprietor of the now-defunct Science Fiction Shop in

Manhattan as well as a books, films, and technology reviewer for several

science fiction magazines. Here he examines the history of fantasy fandom among

readers and the ways in which this fandom was changed, expanded, and challenged

by the greater emergence of fantasy in films and television, particularly where

it concerns Star Trek fandom. Searles explains how fantasy first

became a publishing category, the birth of fantasy conventions and how film and

television have changed conventions, the different types of fantasy readers,

differences in expectations between readers and viewers, and the ways in which

films and television have influenced books, and vice versa.

-Searles

(1934-1993) was the proprietor of the now-defunct Science Fiction Shop in

Manhattan as well as a books, films, and technology reviewer for several

science fiction magazines. Here he examines the history of fantasy fandom among

readers and the ways in which this fandom was changed, expanded, and challenged

by the greater emergence of fantasy in films and television, particularly where

it concerns Star Trek fandom. Searles explains how fantasy first

became a publishing category, the birth of fantasy conventions and how film and

television have changed conventions, the different types of fantasy readers,

differences in expectations between readers and viewers, and the ways in which

films and television have influenced books, and vice versa.

--Other

Dimensions: Etc.

-The

miscellany column this month finds the use of the “popular phrase” the

“twilight zone” in a newspaper article from the May 6, 1915 issue of the

Niagara Falls, NY Gazette, an increase in orders for the music examined by Jack

Sullivan in his recently-ended music column, more gargoyle sightings in NYC (right), an

article on a child born “in the twilight zone” when changes in time zones puts

his birthdate at odds with his admittance to the proper school grade, a

limerick by Edward Lear which includes “E.T.,” a frequently-sited article on

the N.A.A.C.P. which contains the term “Twilight Zone,” and a listing of

unusually named cities, towns, and places across the U.S., such as The

Boneyard, Arizona, Midnight, Mississippi, and Skeleton, Oklahoma.

-The

miscellany column this month finds the use of the “popular phrase” the

“twilight zone” in a newspaper article from the May 6, 1915 issue of the

Niagara Falls, NY Gazette, an increase in orders for the music examined by Jack

Sullivan in his recently-ended music column, more gargoyle sightings in NYC (right), an

article on a child born “in the twilight zone” when changes in time zones puts

his birthdate at odds with his admittance to the proper school grade, a

limerick by Edward Lear which includes “E.T.,” a frequently-sited article on

the N.A.A.C.P. which contains the term “Twilight Zone,” and a listing of

unusually named cities, towns, and places across the U.S., such as The

Boneyard, Arizona, Midnight, Mississippi, and Skeleton, Oklahoma.

--‘‘‘The

Evil Dead’ Why you haven’t seen it yet . . . and why you ought to” by Stephen

King

“While on the scene at Cannes, the

author stumbled upon – well, not gold, exactly,

but plenty of great gore.

-This

is one of the more notable reviews in horror film history. King’s review of

director Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead resulted from the author having attended a

screening of the film at the Cannes Film Festival where the film screened out

of competition. King’s quote of “the most ferociously original horror film of

the year” was used on the film’s theatrical release poster and other marketing

material. The quote was as follows: “that he has made the most ferociously

original horror film of 1982 seems to me beyond doubt.” King uses the word

“genius” when discussing the film and its director while also acknowledging the

film’s derivative nature and its debt to such films as Night of the Living

Dead and The Exorcist. When King viewed the film at Cannes, it

was still struggling to find theatrical distribution and had only been viewed

at occasional screenings. The film was eventually released simultaneously in

theaters by New Line Cinema and on VHS home video. It has become a classic of

the modern horror film, spawning two sequels, Evil Dead II (1987) and Army of Darkness (1992), a television series, Ash vs Evil

Dead (2015-2018), comic books, toys, and

more. The production of the film has been exhaustively documented in

publications like Fangoria as well as

in supplementary material on the film’s various home video releases. King’s

review is a bit of production history, a bit of introduction to the filmmakers

and performers, a bit of detail about the film’s struggle for distribution, and

a bit of critique.

-This

is one of the more notable reviews in horror film history. King’s review of

director Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead resulted from the author having attended a

screening of the film at the Cannes Film Festival where the film screened out

of competition. King’s quote of “the most ferociously original horror film of

the year” was used on the film’s theatrical release poster and other marketing

material. The quote was as follows: “that he has made the most ferociously

original horror film of 1982 seems to me beyond doubt.” King uses the word

“genius” when discussing the film and its director while also acknowledging the

film’s derivative nature and its debt to such films as Night of the Living

Dead and The Exorcist. When King viewed the film at Cannes, it

was still struggling to find theatrical distribution and had only been viewed

at occasional screenings. The film was eventually released simultaneously in

theaters by New Line Cinema and on VHS home video. It has become a classic of

the modern horror film, spawning two sequels, Evil Dead II (1987) and Army of Darkness (1992), a television series, Ash vs Evil

Dead (2015-2018), comic books, toys, and

more. The production of the film has been exhaustively documented in

publications like Fangoria as well as

in supplementary material on the film’s various home video releases. King’s

review is a bit of production history, a bit of introduction to the filmmakers

and performers, a bit of detail about the film’s struggle for distribution, and

a bit of critique.

--John

Carpenter: Doing His Own Thing by James Verniere

“With Firestarter still ahead, The

Thing’s director talks about his lifelong love of horror movies, the spate

of films spawned by his Halloween, and

the perils of remaking – or appearing to remake – a cult classic.”

-James

Verniere provides a concise but detailed account of John Carpenter’s career

before getting into the interview. He begins by asking the director about his

formative years, from an early childhood interest in film and horror to his

university days at the USC film school. Each of Carpenter’s films is then

discussed in turn, from the early film Dark

Star, made for $60,000 while at USC, to

the critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful action thriller Assault

on Precinct 13, to the awesomely successful

Halloween, and concluding with

discussions of Escape from New York, The Fog, and the recently completed The Thing. Each film is discussed in the context of Carpenter’s inspiration,

process, and sociological view. Carpenter clarifies his level of participation

in Halloween II, details what viewers

can expect from Halloween III, and provides

his view on the spate of slasher films which arrived in the wake of Halloween’s

success. Carpenter speaks in detail about

The Thing, from the impetus to remake

a classic to his approach in updating the material. The interview concludes

with Carpenter discussing film projects he planned to make. These projects were

either made much later, never made, or were made without Carpenter’s

involvement, including The Philadelphia Experiment (made in 1984 without Carpenter’s involvement), a weird western titled El Diablo (released in 1990 with Carpenter as

co-writer and executive producer), and, most tantalizingly, an adaptation of

Stephen King’s Firestarter, which was

made without Carpenter’s involvement in 1984.

-James

Verniere provides a concise but detailed account of John Carpenter’s career

before getting into the interview. He begins by asking the director about his

formative years, from an early childhood interest in film and horror to his

university days at the USC film school. Each of Carpenter’s films is then

discussed in turn, from the early film Dark

Star, made for $60,000 while at USC, to

the critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful action thriller Assault

on Precinct 13, to the awesomely successful

Halloween, and concluding with

discussions of Escape from New York, The Fog, and the recently completed The Thing. Each film is discussed in the context of Carpenter’s inspiration,

process, and sociological view. Carpenter clarifies his level of participation

in Halloween II, details what viewers

can expect from Halloween III, and provides

his view on the spate of slasher films which arrived in the wake of Halloween’s

success. Carpenter speaks in detail about

The Thing, from the impetus to remake

a classic to his approach in updating the material. The interview concludes

with Carpenter discussing film projects he planned to make. These projects were

either made much later, never made, or were made without Carpenter’s

involvement, including The Philadelphia Experiment (made in 1984 without Carpenter’s involvement), a weird western titled El Diablo (released in 1990 with Carpenter as

co-writer and executive producer), and, most tantalizingly, an adaptation of

Stephen King’s Firestarter, which was

made without Carpenter’s involvement in 1984.

--“Hell

Is Murky” by John Alfred Taylor

Illustrated by Steve Byram

“They say it’s nice to have a cult

following. But not this kind of

following. And not this cult.”

-A

cartoonist recently moved to Los Angeles believes himself the victim of an

insidious cult whose agents stalk him and whose powers extend to altering

reality. When he discovers a notebook belonging to a cult member in his new

home he sets up a fateful meeting with the cult’s leader.

-A

cartoonist recently moved to Los Angeles believes himself the victim of an

insidious cult whose agents stalk him and whose powers extend to altering

reality. When he discovers a notebook belonging to a cult member in his new

home he sets up a fateful meeting with the cult’s leader.

-This

was an excellent and creative story which struck that otherworldly chord which

will appeal to TZ fans. The imagery is David Lynchian in its approach and the

snap ending is capably handled. John Alfred Taylor (b. 1931) previously

appeared in the pages of TZ with the story “When the Cat’s Away . . .” in the

September, 1981 issue. Taylor appeared again with “Like a Black Dandelion” in

the Sept/Oct, 1983 issue and “The Weight of Zero” in the Jan/Feb, 1985 issue. Taylor

is a prolific short fiction writer, mainly of horror and dark fantasy fiction,

the best of which was collected by Ash Tree Press in the 2008 volume Hell Is Murky: Twenty Strange Tales. “Hell Is Murky” was reprinted in the Summer,

1985 issue of Night Cry.

--Required

Reading: “Levitation” by Joseph Payne Brennan

Illustrated by Edward Gorey

“A classic tale in which we learn that

the supernatural world has its own merciless version of Murphy’s Law.”

-A

hypnotist at a country fair challenges a heckler to come on stage and subject

himself to the trick of levitation. When the hypnotist has a heart attack

during the trick, the unconscious, levitating man continues to rise into the

night sky.

-Joseph

Payne Brennan (1918-1990) was the last great name in horror fiction to emerge

from the pages of Weird Tales, selling a handful of stories to the pulp

magazine between 1952 and its demise in 1954. He is a personal favorite of mine

and, though his work can be difficult to find, I highly recommend Brennan to

anyone who enjoys well-told, traditional tales of horror and mystery. Brennan

was also a prolific and award-winning poet, a mystery writer whose stories

appeared regularly in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, an essayist and expert on the works of H.P.

Lovecraft, and worked for forty years as an acquisitions assistant at Yale’s

Sterling Memorial Library. “Levitation” first appeared in Brennan’s 1959 Arkham

House collection Nine Horrors and a Dream, published in paperback in 1962 with a memorable cover by Richard Powers.

The collection was reprinted in 2019 by Dover. The Edward Gorey illustration

first accompanied the tale with its appearance in the 1968 anthology Hauntings:

Tales of the Supernatural, edited by

Henry Mazzeo. The story was adapted for the first season of Tales from the

Darkside from a script by David Gerrold,

directed by John Harrison, broadcast May 19, 1985. Brennan’s stories “Murder on

the Rocks” and “Goodbye, Dr. Bliss” were adapted for the second season of Boris

Karloff’s Thriller as “The Lethal

Ladies,” scripted by Boris Sobelman, directed by Ida Lupino, broadcast April

16, 1962.

|

| Cover by Kirk Reineret illustrating "Slime" |

-Nine Horrors and a Dream also included much of Brennan’s best work,

including the unforgettable “Slime,” a 1953 Weird Tales cover story which was likely an inspiration

for the film The Blob (1958), “The

Calamander Chest,” about a beckoning, ghostly finger, “Canavan’s Back Yard,”

about a deadly plot of land and a witch’s curse (Brennan wrote a sequel to the

tale, “Canavan Calling,” in 1985), and “The Mail for Juniper Hill,” a devilish

tale of life beyond death. Much of Brennan’s output was self-published by his

Macabre House imprint under which Brennan also published a Weird Tales-like magazine titled Macabre for nearly twenty years between 1957 and

1976. Along with Nine Horrors and a Dream, Brennan’s most readily available collection is The Shapes of

Midnight (Berkley, 1980; reprinted by

Dover in 2019 minus two tales). The original edition included an introduction

from Stephen King in which King admitted Brennan’s influence on his own work:

“Joseph Payne Brennan is one of the most effective writers in the horror genre,

and he is certainly one of the writers I have patterned my own career upon.”

King appropriated the name of a fictional town in Brennan’s works, Juniper

Hill, for the name of the fictional insane asylum in his own works. The

Shapes of Midnight included such stories

as “The Corpse of Charlie Rull,” a fast-paced, gruesome, and undeservedly

neglected zombie tale, “The Willow Platform,” a tale of ironic revenge in the

style of E.C. Comics, “The Horror at Chilton Castle,” a tale of a vampire

legacy, and the Twilight Zone-esque

“The House on Hazel Street,” in which a woman is drawn into the past through

the power of her memories.

--“The

Opening” by Bruce Boston

Illustrated by Annie Alleman

“They were strangers in the night. And

one of them was very strange.”

-After

a fight with his wife, a man walks to a hillside in the nighttime where he is

soon joined by an odd-looking man walking an odd-looking dog. The odd-looking

man talks about the stars and the opportunity to voyage to outer space for

anyone willing to take the journey. Later, the man believes the encounter to

have been a dream, until he finds his wife missing.

-After

a fight with his wife, a man walks to a hillside in the nighttime where he is

soon joined by an odd-looking man walking an odd-looking dog. The odd-looking

man talks about the stars and the opportunity to voyage to outer space for

anyone willing to take the journey. Later, the man believes the encounter to

have been a dream, until he finds his wife missing.

-This

was a slight but enjoyable story with a snap ending from Bruce Boston (b.

1943), who is likely the most honored modern speculative poet. His poetry has

won multiple Rhysling, Asimov’s Readers’, and Bram Stoker Awards as well as the

first Grandmaster Award from the Science Fiction Poetry Association. Boston is

equally adept at prose and his stories have appeared in numerous magazines,

large and small press alike. “The Opening” was collected in Skin Trades (1988).

--TZ

Screen Preview: Halloween III by

James Verniere

“This year’s entry in the seasonal

horror sweepstakes combines Celtic magic, microchips, and masks that transform

more than just your looks. James Verniere reports.”

-Verniere

begins with a potted history of Halloween, the holiday, before moving on to a brief examination of the

first two Halloween films. Halloween III, of course, is remembered as the Halloween

film without the masked killer Michael

Myers. Instead, the plot focuses on the machinations of an evil mask-maker, played to perfection by Dan O'Herlihy, whose products transform and kill those who wear them. The film was initially poorly

received but its reputation has improved in recent years as it has found a new

and appreciative audience. The Halloween franchise was initially intended as an anthology film series, wherein

each film would tell a different story set on Halloween. The popularity of the

Michael Myers character was such that the Halloween films soon settled into a convoluted storyline to keep Myers

terrorizing the town of Haddonfield, Illinois. Though uncredited in the

finished film, Halloween III was

co-scripted by Nigel Kneale, the British scriptwriter best-known for the Quatermass

films and television productions such as The

Stone Tape (1972) and the short-lived

anthology series Beasts. Verniere

gets behind Kneale’s process on scripting the third Halloween film and gets John Carpenter’s input on the

proceedings as well. Finally, first-time director Tommy Lee Wallace, who

previously served under Carpenter as editor and production designer, is briefly

profiled. Wallace went on to direct three episodes of the first revival Twilight

Zone series: “Dreams for Sale,” “Little

Boy Lost,” and “The Leprechaun-Artist,” all from the first season.

-Verniere

begins with a potted history of Halloween, the holiday, before moving on to a brief examination of the

first two Halloween films. Halloween III, of course, is remembered as the Halloween

film without the masked killer Michael

Myers. Instead, the plot focuses on the machinations of an evil mask-maker, played to perfection by Dan O'Herlihy, whose products transform and kill those who wear them. The film was initially poorly

received but its reputation has improved in recent years as it has found a new

and appreciative audience. The Halloween franchise was initially intended as an anthology film series, wherein

each film would tell a different story set on Halloween. The popularity of the

Michael Myers character was such that the Halloween films soon settled into a convoluted storyline to keep Myers

terrorizing the town of Haddonfield, Illinois. Though uncredited in the

finished film, Halloween III was

co-scripted by Nigel Kneale, the British scriptwriter best-known for the Quatermass

films and television productions such as The

Stone Tape (1972) and the short-lived

anthology series Beasts. Verniere

gets behind Kneale’s process on scripting the third Halloween film and gets John Carpenter’s input on the

proceedings as well. Finally, first-time director Tommy Lee Wallace, who

previously served under Carpenter as editor and production designer, is briefly

profiled. Wallace went on to direct three episodes of the first revival Twilight

Zone series: “Dreams for Sale,” “Little

Boy Lost,” and “The Leprechaun-Artist,” all from the first season.

--Country

of the Dead by Randy Chisholm (photos) & John Bensink (text)

“The original ‘silent majority’ – the

dead – may no longer be the majority. And they’re certainly not silent.”

-John

Bensink, who previously appeared in TZ with the story “Midtown Bodies” in the

August, 1982 issue, takes us through some of the more memorable epitaphs

collected in American Epitaphs, Grave

and Humorous by Charles L. Wallis (Dover,

1979), accompanied by evocative photographs from Chisholm. Wallis’ book was

originally published in 1954 by Oxford University Press under the title Stories

on Stone. Examples include:

-John

Bensink, who previously appeared in TZ with the story “Midtown Bodies” in the

August, 1982 issue, takes us through some of the more memorable epitaphs

collected in American Epitaphs, Grave

and Humorous by Charles L. Wallis (Dover,

1979), accompanied by evocative photographs from Chisholm. Wallis’ book was

originally published in 1954 by Oxford University Press under the title Stories

on Stone. Examples include:

On a marker in Paxton, Massachusetts,

for Sidney Ellis, died 1836, age seven weeks:

He

lived

He

wept

He

smiled

He

groaned

And

died.

On a marker in Westernville, New York,

for William Reese, died 1872, age twenty-one:

This

is what I expected but

Not

so soon.

And more of the like.

--“Night

Cry” by Katherine M. Turney

Illustrated by Lisa Mansolillo

“That yowling cat was keeping her awake.

But what if it wasn’t a cat?”

-A

woman is kept awake by a sound outside her apartment window which she cannot

identify. The source of the sound establishes itself in an unexpectedly

gruesome way.

-A

woman is kept awake by a sound outside her apartment window which she cannot

identify. The source of the sound establishes itself in an unexpectedly

gruesome way.

-This

short shocker with a nasty ending was the first, and possibly only, published

story by Katherine M. Turney, whom T.E.D. Klein informs us managed movie

theaters in Denver at the time this story was published. The title of the story

was used for TZ Magazine’s sister publication, Night Cry, which

was published from 1984-1987. Turney’s story was reprinted in the premier issue

of Night Cry, accompanied by an

illustration from D.W. Miller.

--“The

Spook Man” by Al Sarrantonio

Illustrated by Kevin Kelly

“His cape was black, his eyes were

hooded. And he was particularly fond of children.”

-A

figure known as the Spook Man arrives in a small town and entices four

monster-loving children to enter his haunted travelling home. The Spook Man’s

home contains all manner of nightmare creatures and he has built his collection

by transforming the children he brings into his home.

-Al

Sarrantonio (b. 1952) appears again in TZ after last month’s “The Silly Stuff.”

“The Spook Man” is prime Sarrantonio, combining the author’s love of Halloween,

traditional images of horror and the macabre, and an engaging prose style to

create a story which is partly nostalgic sweetness and partly an evocation of

the sinister elements of the dark season. It is also a love letter to those of

us who have always enjoyed monsters and horror stories and the like. Sarrantonio

writes often on the subject of Halloween and “The Spook Man” is clearly an

homage to Ray Bradbury’s many writings on the season, particularly in its

poetic prose style. “The Spook Man” will recall Bradbury’s collection The October Country and, especially, his novel Something Wicked This Way Comes. “The Spook Man” was reprinted in the Fall,

1985 issue of Night Cry and collected

in Toybox (1999).

--“The

Circle” by Lewis Shiner

Illustrated by Peter Kuper

“It was the perfect story for Halloween

– and let the reader beware!”

-A

circle of friends gathers every Halloween night to read scary stories. This

Halloween they receive a package from a fringe member of the group who was

recently pushed out of the circle. The package contains a story to be read

aloud. It concerns the group gathered on Halloween night and the act of reading

the tale traps them in a fateful course of events.

-This

was my favorite story in the issue, a simple yet chilling and exceedingly

clever take on themes ranging from the occult, revenge, the tradition of oral

storytelling, and the politics of social groups. The title refers to the term

used to describe a group of friends as well as the effects of reading the

outcast member’s tale. Lewis Shiner (b. 1950) previously appeared in TZ with the

tales “Blood Relations,” in the May, 1981 issue, and “Tommy and the Talking

Dog” in the July, 1982 issue. “The Circle” was Shiner’s final story for TZ

though he appeared later with a story, “Dancers,” in the Summer, 1987 issue of

TZ’s sister mag, Night Cry. “The Circle” was reprinted in two Halloween

themed anthologies: 13 Horrors of Halloween (1983), edited by Isaac

Asimov, Martin H. Greenberg, and Carol-Lynn Rössel Waugh, and October

Dreams (2000), edited by Richard Chizmar

and Robert Morrish. Chizmar co-scripted a 2009 television adaptation of the

story for the short-lived anthology series Fear Itself. The episode was the final in the series and

did not air on network broadcast but was included when the series was collected

on home video. Chizmar was assisted on the script by Johnathon Schaech and the

episode was directed by Eduardo Rodriguez. The story was collected in Shiner’s Collected

Stories (Subterranean Press, 2009).

--“Halloween

Girl” by Robert Grant

Illustrated by Harry Pincus

“It was the season, the holiday, the

night of nights. And come what may, he was going to spend it with her.”

-A

young boy and a young girl bond over their shared love of monsters, horror, and

Halloween. The young girl grows sick and dies, leaving the young boy forlorn.

The boy grudgingly honors the customs of the next Halloween and afterwards

visits the girl’s grave to leave her his bag of trick-or-treat candy. He wakes

the following morning to evidence that she visited him later in the night.

-This

story was a perfect example of a type of tale which is very hard to write, the

gently spooky story. More touching than chilling, the ending of the tale still

manages to satisfy much in the way of Ray Bradbury’s “The Emissary.” Like Lewis

Shiner’s “The Circle,” Grant’s “Halloween Girl” was reprinted in 13 Horrors of Halloween (1983). Grant appeared later in TZ with the story “Where You Lead . . .

I Will Follow” in the October, 1985 issue.

--“The

Screenplay” by Joseph Cromarty

Illustrated by Yvonne Buchanan

“All this talk about werewolves . . .

could Jack be trying to tell him something?”

-Roger

surprises his friend Jack with a visit to discuss ideas for a screenplay. Jack

seems uncomfortable with Roger’s unexpected visit and becomes increasingly

agitated when Roger suggests a story about werewolves. In fact, Roger begins to

believe that Jack may be a werewolf himself and makes a quick exit. Jack

congratulates himself on being an actor as he got Roger to leave before Roger’s

wife arrived at Jack’s place.

-This

humorous story with an ironic ending is courtesy of Joseph Cromarty

(1932-2016), who previously appeared with the Edgar Allan Poe spoof, “Ms. Found

in a Bottle,” in the August, 1982 issue. Cromarty appeared twice more in TZ,

with “The Neighborhood Assassin” and “Words, Words, Words,” both in the

Jan/Feb, 1984 issue.

--“The

Smell of Cherries” by Jeffrey Goddin

Illustrated by Michael Davis

“Something was spooking the night

watchmen – and it wasn’t robbers. It was just . . .

-A

security guard is terrorized by the frightening revenants which haunt a

warehouse property which was once the site of nerve gas testing.

-Goddin

used his personal experience as a security guard to craft this atmospheric

tale. Anyone can imagine the uneasiness which could creep upon you if you were

left at night to guard an abandoned property. Goddin takes this idea to

horrific heights with some disturbing imagery and great moments of tension. Goddin

is a short story writer who was prolific from the late seventies through the early

nineties, publishing horror and science fiction tales in most of the notable

small press magazines, such as Weirdbook,

Eldritch Tales, Fantasy Tales, Deathrealm, and

the like. His stories have been included in Karl Edward Wagner’s The Year’s

Best Horror Stories, including “The Smell

of Cherries,” which appeared in volume XI of the series (1983). The story was also

reprinted in the anthology A Treasury of American Horror Stories (1985) and collected as the title story of a

2012 volume of Goddin’s stories from Gallows Press. Paperback collectors may know Goddin through his two horror novels

published by Leisure Books, both of which remain collectible for their cover

art: The Living Dead (1987) and Blood

of the Wolf (1987).

--Show-By-Show

Guide: TV’s Twilight Zone: Part Twenty by Marc Scott Zicree

-Marc

Scott Zicree continues his guide to the original television series by providing

cast and crew listings, summaries, and Rod Serling’s opening and closing narrations

for the fifth season episodes “Ninety Years Without Slumbering,” “Ring-a-Ding

Girl,” and “You Drive.”

--TZ

Classic Teleplay: “A Quality of Mercy” by Rod Serling

-The

complete shooting script of Rod Serling’s third season tale about a young,

inexperienced, cruel, and overzealous platoon leader who discovers what it

means to see through the eyes of the enemy. The episode was directed by Buzz

Kulik, starring Dean Stockwell and Albert Salmi, originally broadcast December

29, 1961. Go here for our full review of the episode.

--Looking

Ahead: In December’s TZ

-Next

month looks like another great issue. December’s TZ features stories from David

J. Schow, Pamela Sargent, Mort Castle, and L.P. Hartley, the latter being the

subject of an Essential Writers essay by Jack Sullivan. The issue also features

an interview with director Ridley Scott, a preview of the science

fiction/horror film Xtro, a new quiz from William Fulwiler, and the

script for “Living Doll” by Jerry Sohl, which at this time was still solely

credited to Charles Beaumont. See you next month!

-JP