|

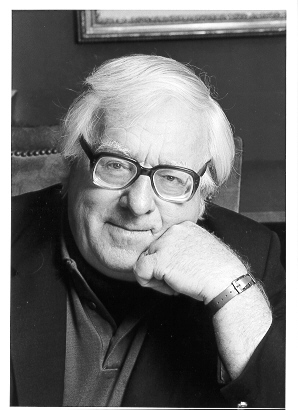

| Portrait of an oddball: Orson Bean as the eternally awkward Mr. James B. W. Bevis |

Season One, Episode 33

Original Air Date: June 3, 1960

Cast:

James B. W. Bevis: Orson BeanJ. Hardy Hempstead: Henry Jones

Mr. Peckinpaugh: Charles Lane

Bartender: Horace McMahon

Landlady: Dorothy Neuman

Margaret: Florence MacMichael

Policeman: William Schallert

Policeman #2: House Peters, Jr.

Young Lady: Colleen O’Sullivan

Peddler: Vito Scotti

Little Boy: Tommy Cletro

Crew:

Writer: Rod Serling (original teleplay)Director: William Asher

Producer: Buck Houghton

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson

Director of Photography: George T. Clemens

Art Direction: George W. Davis and Merrill Pye

Set Decoration: Henry Grace and Keogh Gleason

Assistant Director: Don Klune

Editor: Bill Mosher

Sound: Franklin Milton and Philip Mitchell

Music: Stock

“Next week you’ll meet the occupant of this desk, whose name is James B. W. Bevis, a warm and winning twentieth century oddball about a mile and a half from the norm. He likes things like zither music, little kids and stuff like this. Orson Bean stars next week on the Twilight Zone as Mr. Bevis, and Henry Jones plays his guardian angel. He’s this kind of oddball.”

Rod Serling Opening Narration:

"In the parlance of the twentieth century, this is an oddball. His name is James B. W. Bevis and his tastes lean towards stuffed animals, zither music, professional football, Charles Dickens, moose heads, carnivals, dogs, children and young ladies. Mr. Bevis is accident prone, a little vague, a little discombooberated, with a life that possesses all the security of a floating crap game. But this can be said about Mr. Bevis: without him—without his warmth, without his kindness—the world would be a considerably poorer place, albeit perhaps, a little saner. Should it not be obvious by now, James. B. W. Bevis is a fixture in his own private, optimistic, hopeful little world, a world that has long ceased being surprised by him. James B. W. Bevis, on whom dame fortune will shortly turn her back, but not before she gives him a paste on the mouth. Mr. James B. W. Bevis, just one block away…from the Twilight Zone.”

Summary:

James B. W. Bevis, an inattentive, disaster-prone young man with a warm heart, sets about on his usual morning routine which includes playing catch with the children from his neighborhood and driving his 1924 Rickenbacker to work. After arriving thirty minutes late he is called into the boss’s office, reprimanded, and informed that he is no longer employed with the company. Bevis then realizes that his car has rolled down street and crashed into a light post. When he finally returns to his apartment his landlord informs him that he is being evicted. With nowhere left to turn Bevis heads for the nearest bar.While drowning his sorrows in alcohol Bevis spots the reflection of a man sitting behind him in the mirror behind the bar. The man waves to Bevis but when Bevis turns to look at him he isn’t there. He motions for Bevis to come join him in the booth. Suddenly, the man materializes out of thin air. Bevis, believing himself to be drunk, goes along with it. The stranger introduces himself as Mr. J. Hardy Hempstead, Bevis’s guardian angel. He claims he wants to help Bevis, as it is obvious that Bevis cannot help himself. He gives Bevis the opportunity to relive the day as a new man. Mildly amused, Bevis agrees.

Bevis then wakes up in his apartment. He immediately notices differences. His apartment is clean and his clothes are much nicer. Bevis inquires to Hempstead as to why his apartment looks so different. Hempstead says that it takes sophistication to get ahead in the world and a sophisticated man does not indulge in things like zither music or children’s toys and he does not dress in the fashions that Bevis is accustomed to. Outside, Bevis tries to enter into a game of catch with the neighborhood children but instead they treat him like a total stranger. Hempstead says that the new Bevis no longer plays children’s games. He does not have the time. The new Bevis also does not drive a broken-down Rickenbacker that randomly crashes into light poles. Instead he drives a brand new sports car. At work Bevis notices that his desk does not contain any of the familiar trinkets that are so important to him. He tells Hempstead that he appreciates the effort but that he simply does not like being the new James B. W. Bevis. He doesn't want success if it means abandoning all of the things he cares about. He respectfully asks to be changed back to the old Bevis. Hempstead obliges.

Bevis ends up back at the bar. When he runs out of money he walks outside and sees he Rickenbacker, no longer wrecked, waiting for him at the curb. He realizes that Hempstead is still watching out for him. Then he sees a police officer writing him a ticket for parking in front of a fire hydrant. As he is being thoroughly reprimanded by the officer the fire hydrant suddenly disappears and reappears well away from Bevis’s car. The officer is baffled. Bevis nods to Hempstead and concedes that the fire hydrant bit was a nice touch. Then he gets in his car and drives back to his wonderful life.

“Mr. James B. W. Bevis, who believes in a magic all his own.The magic of a child’s smile, the magic of liking and being liked, the strange and wondrous mysticism that is the simple act of living.James B. W. Bevis, species of twentieth-century male, who has his own private and special Twilight Zone.”

By now we have probably made it more than clear that comedy was not something The Twilight Zone did very successfully. In most cases it simply just didn’t fit the atmosphere of the show. There are pleasant exceptions throughout the show’s five year run but “Mr. Bevis” is not one of them. Stilted and predictable, it’s simply too hokey to be effective. To twist the knife a bit it has the unfortunate luck to be sandwiched between “A Passage for Trumpet” and “The After Hours” which are regarded by most as two of the best efforts from the first season. Before going any further it is probably a good place to note that Orson Bean, Buck Houghton, and Rod Serling all considered this episode to be more or less a forgettable failure.

Serling may have taken the poor reception of this episode harder than everyone else involved because he had intended it to be the pilot for a half-hour comedy series for CBS. The series would see a clumsy protagonist getting himself into various situations every week with a guardian angel having to rescue him. This is not a bad premise and would have possibly made a charming situational comedy but, unfortunately, the finished product just does not work. Serling’s dialogue seems forced and the humor uninspired. Likewise, director William Asher (of I Love Lucy and Bewitched fame) does little to enhance a poor script and the episode feels flat and choppy.

Despite Serling’s disappointment with this episode he would recycle elements of this story for two later episodes of the show, season two's "The Whole Truth" and season three's "Cavender is Coming." Unfortunately, his efforts on these episodes would bring similar results and neither is regarded very highly. When scripting "The Whole Truth" Serling re-used several plot elements from his abandoned "Mr. Bevis" series including an episode in which Bevis is introduced to a guardian angel who is unable to tell a lie and another episode in which Bevis gets a job as a used car salesman. At the end of the third season, after learning that rising comedy star Carol Burnett was interested in appearing on the show, Serling was faced with a great opportunity but not much time in which to write a script that would showcase Burnett's talents. As an added pressure CBS expressed a desire to possibly use the episode as the pilot for a comedy series and increased the production budget and lengthened the shooting schedule. Serling decided to try his hand at the "Mr. Bevis" script one last time. This time, however, he decided that the focus should be placed on the angel and not the recipient of his good deeds. So "Cavender is Coming" was actually a vehicle for a series which would star Jesse White, who plays the angel, and not the clumsy but lovable young woman played by Burnett. This is why White gets top billing in the episode even though Burnett is clearly the lead.

“Mr. Bevis” is Orson Bean’s only appearance on the program. Throughout his career, which spans over six decades, Bean has made a name for himself as a dependable comedic performer. His film and television credits include Anatomy of a Murder (1958) with James Stewart, the voice of Bilbo Baggins in the 1970’s animated films The Hobbit (1977) and The Return of the King (1980), a regular role on Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman (1993-1998), Being John Malkovich (1999) and a reoccurring role on Desperate Housewives.

This episode marks the only appearance by Henry Jones as well. Jones had a highly versatile career as a character actor on Broadway in the 1940’s before making his way into film and television. His big break came when he starred in both the stage and film versions of Maxwell Anderson’s play The Bad Seed (1958). Other notable film roles include 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), Nine to Five (1980), Deathtrap (1982), Dick Tracy (1990), Arachnophobia (1990) and The Grifters (1990). His television appearances include Thriller, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Rod Serling’s Night Gallery, Gunsmoke, Kolchak: the Night Stalker, The Six Million Dollar Man, and Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color. But he is probably best known as the coroner in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). Jones died in 1999 at the age of 86.

There is really not much to say about this episode and not many reasons to recommend it to anyone. It does, however, have a handful of slightly charming and quirky moments which saves it from being completely unwatchable. Still, if you are new to the show and want to start with the best and work your way down it will be quite a long time before you make your way to “Mr. Bevis.”

Grateful acknowledgement is made to:

The Twilight Zone: Unlocking the Door to a Television Classic by Martin Grams, Jr. (OTR Publishing, 2008)

Notes:

-William Schallert also appeared in the first revival Twilight Zone series episode "Shadow Play," a remake of the original episode written by Charles Beaumont. Schallert appeared as well in Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), in the third segment, "It's a Good Life."

-Vito Scotti also appeared in the third season episode "The Gift."

-Henry Jones appeared in an episode of Rod Serling's Night Gallery titled "You Can't Get Help Like That Anymore."

-"Mr. Bevis" was adapted into a Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring Bruno Kirby.

-Orson Bean also appeared in the Twilight Zone Radio Drama episode "The Changing of the Guard."

--Brian