|

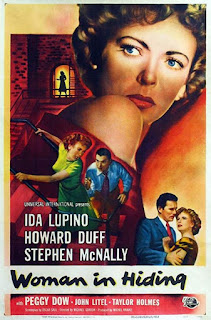

| Illustration by Gregory Cannone for George Clayton Johnson's "All of Us Are Dying" Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine, May, 1982 |

Sources generally agree that John

Huston’s 1941 film The Maltese Falcon, the

third cinematic adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel, was the first

major Film Noir. Sources differ on the end of Film Noir’s classic era. A

frequently cited end date is 1960 and the release of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, based on Robert Bloch’s 1959

novel. Hitchcock borrowed elements from Film Noir (black-and-white cinematography, a

murder mystery, a woman on the run, the grizzled private eye), as he had for such previous films as Strangers on a Train (1951) and The Wrong Man (1956), and delivered a

shocking psycho-sexual nightmare which heralded the arrival of a more daring and

ferocious type of film thriller. One of the most transitional works in the

history of cinema, Psycho was an

enormous influence on subsequent crime and suspense films, not to mention literature and illustrative arts. A year before Psycho was released to theaters, The Twilight Zone premiered on American

television.

Sources generally agree that John

Huston’s 1941 film The Maltese Falcon, the

third cinematic adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel, was the first

major Film Noir. Sources differ on the end of Film Noir’s classic era. A

frequently cited end date is 1960 and the release of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, based on Robert Bloch’s 1959

novel. Hitchcock borrowed elements from Film Noir (black-and-white cinematography, a

murder mystery, a woman on the run, the grizzled private eye), as he had for such previous films as Strangers on a Train (1951) and The Wrong Man (1956), and delivered a

shocking psycho-sexual nightmare which heralded the arrival of a more daring and

ferocious type of film thriller. One of the most transitional works in the

history of cinema, Psycho was an

enormous influence on subsequent crime and suspense films, not to mention literature and illustrative arts. A year before Psycho was released to theaters, The Twilight Zone premiered on American

television.  Perhaps the most important element on The Twilight Zone was the writers. Series creator Rod Serling, always creatively concerned with the

losers, the dreamers, and the doomed, was naturally at the forefront of the Noir influence on the series, but he also recruited writers who were

sensitive to the literary style from which the cinematic genre was born. Richard

Matheson began his career as a novelist with the James M. Cain-inspired effort Someone Is Bleeding (1953) while Charles

Beaumont and John Tomerlin collaborated (as Keith Grantland) on a novel, Run From the Hunter (1957), which bore

the influence of David Goodis’s 1946 novel Dark

Passage, which likely inspired the man-on-the-run television series The Fugitive (1963-1967). Meanwhile, a

young writer named George Clayton Johnson arrived in Hollywood fresh off the

sale of a film treatment which became the popular, Noir-influenced heist film Ocean’s 11 (1960). These

writers were responsible for the show’s most overtly Noir-influenced

output.

Perhaps the most important element on The Twilight Zone was the writers. Series creator Rod Serling, always creatively concerned with the

losers, the dreamers, and the doomed, was naturally at the forefront of the Noir influence on the series, but he also recruited writers who were

sensitive to the literary style from which the cinematic genre was born. Richard

Matheson began his career as a novelist with the James M. Cain-inspired effort Someone Is Bleeding (1953) while Charles

Beaumont and John Tomerlin collaborated (as Keith Grantland) on a novel, Run From the Hunter (1957), which bore

the influence of David Goodis’s 1946 novel Dark

Passage, which likely inspired the man-on-the-run television series The Fugitive (1963-1967). Meanwhile, a

young writer named George Clayton Johnson arrived in Hollywood fresh off the

sale of a film treatment which became the popular, Noir-influenced heist film Ocean’s 11 (1960). These

writers were responsible for the show’s most overtly Noir-influenced

output. Episodes are listed in order of original broadcast date.

For

his series debut writer Charles Beaumont adapted his story from the October, 1958 issue of Playboy into a tense thriller concerning Edward Hall (Richard Conte), a man with a

heart condition whose overactive imagination has turned his dreaming state deadly.

Hall’s recurring nightmare centers on a carnival roller coaster and the beautiful

but dangerous Maya the Cat Girl. Conte, who built a career

playing gangsters in films such as Under

the Gun (1951) and The Big Combo (1955)

is given the unenviable task of acting manic for half an hour yet pulls it off

brilliantly. Throw in a psychiatrist (John Larch), a seedy carnival, and a femme fatale in the form of Canadian actress Suzanne

Lloyd (in an unforgettable performance as the alluring yet psychopathic Maya

the Cat Girl) and “Perchance to Dream” wears its Noir influence on its sleeve. The

knockout punch is the weird musical score from Nathan Van Cleave and director

Robert Florey’s twisted camera work, which combine to perfectly illuminate Edward Hall’s deteriorating mental state. “Perchance to Dream” is an underrated

episode overall but for those interested in the influence of Film Noir on the

series it is essential viewing.

For

his series debut writer Charles Beaumont adapted his story from the October, 1958 issue of Playboy into a tense thriller concerning Edward Hall (Richard Conte), a man with a

heart condition whose overactive imagination has turned his dreaming state deadly.

Hall’s recurring nightmare centers on a carnival roller coaster and the beautiful

but dangerous Maya the Cat Girl. Conte, who built a career

playing gangsters in films such as Under

the Gun (1951) and The Big Combo (1955)

is given the unenviable task of acting manic for half an hour yet pulls it off

brilliantly. Throw in a psychiatrist (John Larch), a seedy carnival, and a femme fatale in the form of Canadian actress Suzanne

Lloyd (in an unforgettable performance as the alluring yet psychopathic Maya

the Cat Girl) and “Perchance to Dream” wears its Noir influence on its sleeve. The

knockout punch is the weird musical score from Nathan Van Cleave and director

Robert Florey’s twisted camera work, which combine to perfectly illuminate Edward Hall’s deteriorating mental state. “Perchance to Dream” is an underrated

episode overall but for those interested in the influence of Film Noir on the

series it is essential viewing. “What You Need” Season one, Episode 12

Written by Rod Serling, from a story by Henry Kuttner & C.L. Moore, Directed by Alvin Ganzer, Starring Ernest Truex and Steve Cochran (December 25, 1959)

This most overtly Film Noir-influenced episode is a Rod Serling adaptation of an unpublished story by George Clayton Johnson

about a criminal named Arch Hammer who can change his appearance at will. The

tough dialogue is straight out of a paperback novel and the players are Film Noir standbys: the conman, the gangster, the jazz musician, the washed up

boxer, the lonely nightclub singer. The episode’s strength is in the production

design and photography, including a dazzling floating neon sequence. It remains a memorable debut for George Clayton Johnson on the

series, whose jazzy writing was perfectly filtered through Rod Serling’s

remarkable gifts for characterization and dialogue. Johnson’s story was later

published in the October, 1961 issue of Rogue.

This most overtly Film Noir-influenced episode is a Rod Serling adaptation of an unpublished story by George Clayton Johnson

about a criminal named Arch Hammer who can change his appearance at will. The

tough dialogue is straight out of a paperback novel and the players are Film Noir standbys: the conman, the gangster, the jazz musician, the washed up

boxer, the lonely nightclub singer. The episode’s strength is in the production

design and photography, including a dazzling floating neon sequence. It remains a memorable debut for George Clayton Johnson on the

series, whose jazzy writing was perfectly filtered through Rod Serling’s

remarkable gifts for characterization and dialogue. Johnson’s story was later

published in the October, 1961 issue of Rogue. Professional boxing is unquestionably the

sport of choice in Film Noir. In films such as Body

and Soul (1947), The Set-Up (1949), and Champion (1949), boxing is viewed

through the lens of loyalty, honor, criminality, and consequence. Rod Serling’s

writing career was launched into the stratosphere with his Playhouse 90 effort “Requiem for a Heavyweight” (1956), about a washed up boxer trying for a second chance in life, and he

returns here to tackle the sport through a lens of fantasy. The result is a heartbreaking meditation on faith and forgiveness

performed by a groundbreaking group of African American performers who broke through the color lines of American television. It remains one of Serling’s

most underrated efforts on the series and comes highly recommended.

Professional boxing is unquestionably the

sport of choice in Film Noir. In films such as Body

and Soul (1947), The Set-Up (1949), and Champion (1949), boxing is viewed

through the lens of loyalty, honor, criminality, and consequence. Rod Serling’s

writing career was launched into the stratosphere with his Playhouse 90 effort “Requiem for a Heavyweight” (1956), about a washed up boxer trying for a second chance in life, and he

returns here to tackle the sport through a lens of fantasy. The result is a heartbreaking meditation on faith and forgiveness

performed by a groundbreaking group of African American performers who broke through the color lines of American television. It remains one of Serling’s

most underrated efforts on the series and comes highly recommended. Director Douglas Heyes was up to the

challenge for this technically challenging two-man play showcasing Rod Serling’s

concerns with the doomed and the redeemed. It is another example of Serling’s

ability to combine the crime drama with fantasy as Joe Mantell plays a cowardly

small-time crook who comes face-to-face with the hidden self beneath the

surface. William D. Gordon, later to play the lead doctor in Serling’s

masterpiece, “Eye of the Beholder,” is suitably slimy as an antagonistic thug. Though

clearly influenced by Film Noir, Serling’s redemptive ending is unique in a typically nihilistic genre.

Director Douglas Heyes was up to the

challenge for this technically challenging two-man play showcasing Rod Serling’s

concerns with the doomed and the redeemed. It is another example of Serling’s

ability to combine the crime drama with fantasy as Joe Mantell plays a cowardly

small-time crook who comes face-to-face with the hidden self beneath the

surface. William D. Gordon, later to play the lead doctor in Serling’s

masterpiece, “Eye of the Beholder,” is suitably slimy as an antagonistic thug. Though

clearly influenced by Film Noir, Serling’s redemptive ending is unique in a typically nihilistic genre. Functioning almost as a darkly humorous remake

of George Clayton Johnson’s “The Four of Us Are Dying,” “Dead Man’s Shoes”

finds bum Nate Bledsoe (Warren Stevens) steal a pair of shoes off a murdered

gangster who’s been dumped in an alley. A game of switched identities ensues as

Bledsoe becomes the murdered man as long as he wears the shoes. Warren Stevens’s

deadpan acting style perfectly complements Montgomery Pittman’s direction as

does the jazz-inflected cues from the stock music. The supporting cast is rounded out by

Richard Devon as a long-faced mobster and the statuesque Joan Marshall as the

dead gangster’s girl. “Dead Man’s Shoes” was remade, as the

entertaining “Dead Woman’s Shoes,” for the first revival Twilight Zone series in 1985.

Functioning almost as a darkly humorous remake

of George Clayton Johnson’s “The Four of Us Are Dying,” “Dead Man’s Shoes”

finds bum Nate Bledsoe (Warren Stevens) steal a pair of shoes off a murdered

gangster who’s been dumped in an alley. A game of switched identities ensues as

Bledsoe becomes the murdered man as long as he wears the shoes. Warren Stevens’s

deadpan acting style perfectly complements Montgomery Pittman’s direction as

does the jazz-inflected cues from the stock music. The supporting cast is rounded out by

Richard Devon as a long-faced mobster and the statuesque Joan Marshall as the

dead gangster’s girl. “Dead Man’s Shoes” was remade, as the

entertaining “Dead Woman’s Shoes,” for the first revival Twilight Zone series in 1985.Written by Rod Serling, Directed by Joseph M. Newman, Starring Jack Klugman and Bill Mumy (September 27, 1963)

This affecting drama concerns an alcoholic bookmaker, Max Phillips, who receives a telegram informing him that his son the soldier, Pip, is wounded and dying in South Vietnam. Max is shot during a confrontation with a crime boss and wanders wounded into an amusement park after hours. Amazingly, Max meets his son in the deserted park, but Pip is somehow ten years old again. They spend a wonderful hour together before Pip has to leave and return to his adult body to die. Max is filled with regret for a lifetime of poor parenting and makes a deal with God, his life for Pip’s. Max dies and Pip survives. Rod Serling’s powerful meditation on parental love is anchored by a potent performance from Jack Klugman and juxtaposed against the seedy underworld of two-bit bookies and conmen. The moody atmosphere of the deserted amusement park and the mournful, jazz-inflected score by Rene Garriguenc (conducted by Lud Gluskin) add a haunting, noir-ish quality to the drama. Workmanlike director Joseph M. Newman was no stranger to Film Noir, having directed 711 Ocean Drive (1950), Lucky Nick Cain (1951), Dangerous Crossing (1953), and The Human Jungle (1954), as well as several episodes of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

“The Last Night of a Jockey” Season five, Episode 125

Written

by Rod Serling, directed by Joseph M. Newman, starring Mickey Rooney (October 25, 1963)

Thematically related to "Nervous Man in a Four Dollar Room," and taking place in one of the most noir-ish of settings, a flea-bitten one-room apartment, Rod Serling’s morality tale is that of Grady, a diminutive jockey who loses his livelihood when caught doping horses. Now he wallows in his own grief and anger, until he is visited by his alter ego, an impish double who appears to first taunt Grady and then to grant Grady’s wish to be big. Grady becomes a giant, steadily growing from first eight feet tall then ten feet tall. When the head of the racing commission telephones to inform Grady that he’s been cleared to ride again, Grady realizes with horror that he’s now too big to ride. His most fervent wish has sealed his doom. It doesn’t get more noir than that.

As Film Noir moved into the fifties so did

the genre’s preoccupation with the Cold War. “The Jeopardy Room” combines Rod

Serling’s talent for social commentary and characterization while also

remaining an entertaining espionage thriller. Serling cuts the fat off the

typical spy tale and gets right to a game of cat and mouse staged between two motel rooms. If

the narrative jumps logic in a few spots it is suited to the type of pulp novel on screen Serling and company were trying to achieve. Although this episode

is sometimes dismissed as a tale better suited to Alfred Hitchcock Presents, it is

unmistakably the work of Rod Serling and displays the range of the series.

Director Richard Donner was the last great director to arrive on the series and

here shows his skill in staging a violent and paranoid thriller. Donner

embraces the staged quality of the script with some innovative camera work which keeps the dialogue-heavy action moving forward. The episode also benefits from the presence of Martin Landau, one of the finest actors of

his generation, and John Van Dreelen in a pleasingly over-the-top performance

as the villainous Commissar Vassiloff.

As Film Noir moved into the fifties so did

the genre’s preoccupation with the Cold War. “The Jeopardy Room” combines Rod

Serling’s talent for social commentary and characterization while also

remaining an entertaining espionage thriller. Serling cuts the fat off the

typical spy tale and gets right to a game of cat and mouse staged between two motel rooms. If

the narrative jumps logic in a few spots it is suited to the type of pulp novel on screen Serling and company were trying to achieve. Although this episode

is sometimes dismissed as a tale better suited to Alfred Hitchcock Presents, it is

unmistakably the work of Rod Serling and displays the range of the series.

Director Richard Donner was the last great director to arrive on the series and

here shows his skill in staging a violent and paranoid thriller. Donner

embraces the staged quality of the script with some innovative camera work which keeps the dialogue-heavy action moving forward. The episode also benefits from the presence of Martin Landau, one of the finest actors of

his generation, and John Van Dreelen in a pleasingly over-the-top performance

as the villainous Commissar Vassiloff. -JP

What a cool idea for a post! I must admit I like the first season's noir shows best of this group. I also LOVE Noir Alley and record and watch it weekly. Thanks for reminding me of some of these great episodes.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Jack! The first season was definitely the most Noir influenced of the series. The show only occasionally came back to that style afterwards. There were also many episodes which looked Noir but were more science fiction in nature so I left them off the list. Thanks for reading!

Delete