|

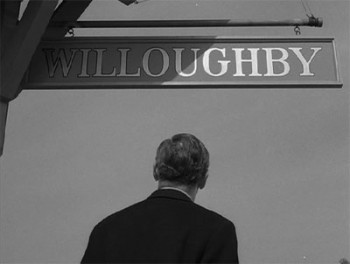

| Gart Williams (James Daly) longs for escape to Willoughby |

"A Stop at Willoughby"

Season One, Episode 30

Original Air Date: May 6, 1960

Cast:

Gart Williams: James Daly

Jane Williams: Patricia Donahue

Mr. Misrell: Howard Smith

Young Conductor: Jason Wingreen

Old Conductor: James Maloney

Helen: Mavis Neal

Man on Wagon: Max Slaten

Boy One: Billy Booth

Boy Two: Butch Hengen

Trainman: Ryan Hayes

Crew:

Writer: Rod Serling (original teleplay)

Director: Robert Parrish

Producer: Buck Houghton

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson

Director of Photography: George T. Clemens

Art Direction: George W. Davis and Merrill Pye

Set Decoration: Henry Grace and Keogh Gleason

Assistant Director: Don Klune

Editor: Joseph Gluck

Sound: Franklin Milton and Philip Mitchell

Art Direction: George W. Davis and Merrill Pye

Set Decoration: Henry Grace and Keogh Gleason

Assistant Director: Don Klune

Editor: Joseph Gluck

Sound: Franklin Milton and Philip Mitchell

Music: Nathan Scott

And Now, Mr. Serling:

"This old-fashioned railroad car is about as extinct as the dinosaur but next week it takes us to a little village that is not only a place but a state of mind. It's the transportation to what we think is one of the most unique stories we've ever presented. Next week, Mr. James Daly stars in 'A Stop at Willoughby.' We hope you stop with him. Thank you and good night."

Rod Serling's Opening Narration:

"This is Gart Williams, age thirty-eight, a man protected by a suit of armor all held together by one bolt. Just a moment ago, someone removed the bolt and Mr. Williams' protection fell away from him and left him a naked target. He's been cannonaded this afternoon by all the enemies of his life. His insecurity has shelled him, his sensitivity has straddled him with humiliation, his deep-rooted disquiet about his own worth has zeroed in on him, landed on target, and blown him apart. Mr. Gart Williams, ad agency exec, who in just a moment will move into The Twilight Zone in a desperate search for survival."

Summary:

Advertising executive Gart Williams sits at a table in the conference room of a high rise office suite surrounded by other middle-aged men. Gart is nervous, his hands moving in dreaded anticipation. At the opposite end of the table from Gart is an older, rotund gentleman, the owner of the agency, Mr. Misrell, who sits smoking a large cigar and looking perturbed. The men sit for a moment in silence until Mr. Misrell breaks it. He demands to know where another advertising man is, a young protégé of Gart's named Jake Ross that Gart has put in charge of a very important account. Ross is already over half an hour late to the meeting. Gart attempts to make a phone call to find out where Ross is but to no avail. Moments later, a letter arrives. It is a communication from Jake Ross tendering his resignation with Mr. Misrell's agency and taking the important and lucrative account with him.

Mr. Misrell nearly explodes at this bad news. He berates Gart for his lack of sound judgment and lectures him on the nature of the advertising business until Misrell's voice grows in power and force. Gart, at a breaking point, tells Misrell to shut up and storms from the room. Gart grabs at his chest and, ignoring the curious and concerned looks of those around him, closes himself off in his darkened office.

While taking the train out of the city, Gart briefly speaks with the usual conductor and then falls asleep. He soon finds himself awakened by the conductor, a different, older, and curiously dressed conductor, announcing the train stop at a town called Willoughby. Gart is confused by this because everything has changed but it doesn't feel like a dream. Where it was winter it is now summer. Where it was 1960, it is now 1888. The friendly conductor tells Gart these things as Gart gazes out the window at Willoughby, a town which by appearance epitomizes a simpler, slower, more innocent and less stressful time. Gart looks again for the conductor and sees that the man has moved down to the farther cars on the train. Gart gets up and chases after the man. As he is about to step off the train, he finds himself jerked back to reality. He asks the conductor, his normal conductor, about a town called Willougby and the conductor tells Gart that he's never heard of such a town. Gart writes the experience off as a particularly vivid dream.

At home, it is apparent that Gart is not only the victim of an unhappy career but also an unhappy marriage. His wife Jane is a mocking and unhappy woman with a large appetite for the best that money can buy. Her initial fear upon hearing that Gart had a breakdown at work was whether or not it would cost him his job. Gart tells her about his "dream" of Willoughby and his wishes to return to a simpler, slower time. But Jane isn't listening. When her fears about Gart's job security are alleviated, she berates Gart for being a child that has never grown up and walks out of the room.

The next evening, on his way home, Gart again falls asleep on the train and gets a glimpse of Willoughby. He again runs after the conductor, yelling. He is instead awakened by the regular conductor when the man hears Gart calling out in his sleep. Unperturbed, Gart makes a promise to himself that he is going to get off the train at Willougby next time.

After another harrowing day at the office Gart heads for home. On the train he becomes aware that this is his only chance to escape from the horrors of his life. He lowers the blind on the window, closes his eyes, and falls asleep.

When Gart again opens his eyes he sees that the train has stopped at Willoughby. At the encouragement of the conductor, Gart steps off the train. Gart is greeted by the townspeople as though they've known him all his life. Smiling happily, Gart walks off toward the center of town.

Meanwhile, back in 1960, Gart's dead body lies in the snow below the train tracks. According to the conductor, Gart said something about a town called Willoughby and then stepped off the moving train, falling to his death. As a final twist, Gart's body is taken away by a funeral home with a car marked Willoughby & Son.

We close on the image of Gart having fully escaped into his fantasy world, walking toward the bandstand that sits at the center of Willoughby.

Rod Serling's Closing Narration:

"Willoughby? Maybe it's wishful thinking nestled in a hidden part of man's mind, or maybe it's the last stop in the vast design of things, or perhaps, for a man like Gart Williams, who climbed on a world that went by too fast, it's a place around the bend where he could jump off. Willoughby? Whatever it is, it comes with sunlight and serenity, and is a part of The Twilight Zone."

Commentary:

"And then Williams realized that once again he stood in the middle of an old-fashioned train car and, approaching him from the opposite end, was the old conductor with the brass buttons and the old-fashioned cap.

"'Willoughby,' the conductor smiled at him. 'All out for Willoughby.'"

-"A Stop at Willoughby" by Rod Serling, More Stories from the Twilight Zone (Bantam, 1961)

"And then Williams realized that once again he stood in the middle of an old-fashioned train car and, approaching him from the opposite end, was the old conductor with the brass buttons and the old-fashioned cap.

"'Willoughby,' the conductor smiled at him. 'All out for Willoughby.'"

-"A Stop at Willoughby" by Rod Serling, More Stories from the Twilight Zone (Bantam, 1961)

|

| James Maloney as the Conductor for the Willoughby train |

Serling initially felt, incredibly, that "Walking Distance" was an all-around failure of an episode, though he would later come to recognize the episode's qualities. He had the general plot of "A Stop at Willoughby" in mind at the very beginning of The Twilight Zone’s creation and likely pushed the script into production so soon after the airing of "Walking Distance" because he felt the first episode had inadequately conveyed the theme he was attempting to bring across. "A Stop at Willoughby," however, lacks the impact and emotional resonance of "Walking Distance" due mainly to inflated characterizations and a baffling twist-in-the-tale ending.

The major problem with "A Stop at Willoughby" is that it is characteristically over-the-top. Whereas "Walking Distance" perfectly struck a nostalgic, melancholy tone, "A Stop at Willoughby" is instead depressing, filled with unlikable and unbelievable characters. Though James Daly is excellent as Gart Williams, both his high-pressure boss and his gold-digging wife are gross caricatures. The entire episode is the equivalent of watching Gart Williams bounce from one stress inducing obstacle to another with intermittent scenes of his gradual passage into a fantasy land which feels artificial and bizarre. Serling perhaps should have portrayed a fantasy which had no such immediately recognizable place within American history. Show the simple nature of an idealized time in the past but there is no need to define it as the summer of 1888 (Serling repeated this tendency in the fourth season episode, "No Time Like the Past," which contains elements of "A Stop at Willoughby").

It also seems a strange choice of escape for the main character, who seems to have no reason for his chosen fantasy other than it is a time that moved slower and in which a man could presumably live his life to the fullest. "Walking Distance" worked much better in this regard as the fantasy is firmly grounded in the character's personal past. The only difference is that, in "Walking Distance" (as well as in "No Time Like the Past"), the main character discovers that you can't go back again to what once was, whether real or imagined. The character of Gart Williams, in “A Stop at Willoughby,” has not even a tenuous relationship to his fantasy. He couldn’t possibly have lived within the time frame of the fantasy and the viewer is given no reason for such a fixation upon this specific time in the past. We also know that life in 1888 was in fact very difficult. It is doubtful that many of us would enjoy living in a time of deeply systemic racism, before women were allowed to vote, before the essentials of modern medicine, dependable sanitation systems, electricity, the automobile, and on and on.

“Walking Distance” is also a more uplifting episode with its fundamental message that only those who look to the past for happiness fail to see the happiness which lies before them. Martin Sloan, in "Walking Distance," realizes that the solution to his problems do not lie in a simple escape into fantasy. The lesson learned is that he controls his own existence and if he needs to slow down to take control of his own life then he can do so. Serling's views on the matter by the time he brought "A Stop at Willoughby" into production seem to have changed as the main character is now the victim of such a powerful onslaught that he has lost all control and is left with no choice but to cling to his fantasy and escape into it even though it may (and in fact does) cost him his real existence. Gart Williams's death becomes a sort of grotesquely symbolic suicide.

It also seems a strange choice of escape for the main character, who seems to have no reason for his chosen fantasy other than it is a time that moved slower and in which a man could presumably live his life to the fullest. "Walking Distance" worked much better in this regard as the fantasy is firmly grounded in the character's personal past. The only difference is that, in "Walking Distance" (as well as in "No Time Like the Past"), the main character discovers that you can't go back again to what once was, whether real or imagined. The character of Gart Williams, in “A Stop at Willoughby,” has not even a tenuous relationship to his fantasy. He couldn’t possibly have lived within the time frame of the fantasy and the viewer is given no reason for such a fixation upon this specific time in the past. We also know that life in 1888 was in fact very difficult. It is doubtful that many of us would enjoy living in a time of deeply systemic racism, before women were allowed to vote, before the essentials of modern medicine, dependable sanitation systems, electricity, the automobile, and on and on.

“Walking Distance” is also a more uplifting episode with its fundamental message that only those who look to the past for happiness fail to see the happiness which lies before them. Martin Sloan, in "Walking Distance," realizes that the solution to his problems do not lie in a simple escape into fantasy. The lesson learned is that he controls his own existence and if he needs to slow down to take control of his own life then he can do so. Serling's views on the matter by the time he brought "A Stop at Willoughby" into production seem to have changed as the main character is now the victim of such a powerful onslaught that he has lost all control and is left with no choice but to cling to his fantasy and escape into it even though it may (and in fact does) cost him his real existence. Gart Williams's death becomes a sort of grotesquely symbolic suicide.

"A Stop at Willoughby" is informed by Serling's personal interactions with advertising executives as he had been in television long enough by this point to run into the constant roadblocks characteristic of advertiser-supported television. What is interesting is that even though Serling turns the general industry of advertising into a villainous leach feeding upon the lifeblood of the working man, he is still able to identify with the alienated individual and use that to examine his own set of moral and ethical ideals.

The episode does have some great dialogue from Serling and fits the half-hour time slot accorded it quite perfectly, with excellent pacing from director Robert Parrish. It's interesting to note here that Serling originally conceived the script as a one-hour play for possible sale to one of the popular anthology programs of the second half of the 1950s. It seems as though had he actually produced the play as a one-hour program, the fantasy construct and the patience of the viewer would both have been stretched to the breaking point.

A quick note on the only aspect of the production side of the episode which was lacking and this concerns the music from composer Nathan Scott. Scott's score seems to flourish whimsically during moments of grave seriousness and then quietly pulse during moments of pure fantasy where the whimsical flourish would be most appropriate. Scott's music was used one other time for the show, in season three's "Young Man's Fancy," a disturbing dark fantasy also concerning the past. It is interesting to think what a composer such as Bernard Herrmann, Nathan Van Cleave, or Jerry Goldsmith would have done with such a fantasy-rich episode.

The ending of the episode is where most of the fault in the script lies. Many times The Twilight Zone was guilty of tacking on a twist ending that had little or no logical reason being there. Unfortunately, "A Stop at Willoughby" is one of these times. It must be assumed that viewers enjoy twist endings for no other reason than the memorable nature of the sudden and ironic change. According to dialogue in "A Stop at Willoughby," Gart Williams got up and stepped off the actual moving train when he decided to get up and step off at the fantasy stop of Willoughby. This doesn't work for two reasons. First, earlier in the episode Gart did get up and walk to the end of the car and onto the deck looking out over Willoughby yet in his real existence he never moved from his seat. From this basis, would it not stand to reason that what Gart did in the fantasy world, what he said, how he moved, would inform what he did in the real world? We were also shown scenes of Gart speaking the same words in both realities. It would have made more sense for Gart to have simply disappeared into the fantasy world, for the conductor to have walked down the aisle and found Gart's seat empty. Additionally, placing the name Willoughby and Son on the back of the hearse makes no sense other than to so serve as a sly, albeit confusing, wink to the viewer. Yes, we know that Gart has gone to Willoughby, but the attempt to have that literal translation in the world of his previous existence is nonsensical. The twist in the episode should always flow logically from the events preceding it.

Prolific actor James Daly began his career on television, appearing frequently on anthology programs, including genre turns on The Clock, Suspense, The Web, Danger, Climax!, and Suspicion before his appearance on The Twilight Zone. Moving into the 1960's and beyond, Daly had roles in some of the most fondly remembered television programs and in some cult fare as well, including Combat!, The Fugitive, Gunsmoke, Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color, Star Trek, Ironside, Mission: Impossible, and The Invaders. He co-starred in the classic 1968 science-fiction film Planet of the Apes (co-written by Rod Serling), playing the role of Honorious. He died on July 3, 1978 in Nyack, New York. Roots: the Next Generation (1979) was his last credited work.

Director Robert Parrish began his career as an actor while still a child, appearing uncredited in such films as the Academy Award winning All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and the Charlie Chaplin film City Lights (1931). He worked on All the King’s Men (1949) and won an Academy Award for editing the 1947 film Body and Soul before moving into the director’s chair with 1951's Cry Danger. He went on to direct several more mid-budget thrillers including the cult-classic A Town Called Hell (1971) starring Telly Slavalas and Robert Shaw. He died on December 4, 1995 on Long Island, New York.

Veteran actor Howard Smith, portraying the villainous Mr. Misrell, made a career playing supporting roles, usually as a police officer or some other authority figure. His film credits include Kiss of Death (1947), Call Northside 777 (1948), The Street with No Name (1948), and A Face in the Crowd (1957). He was a fixture on television from the late 1950's onward with appearances on Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Naked City, Wanted: Dead or Alive, Perry Mason, Green Acres, and Bewitched. He died on January 10, 1968 in Hollywood.

Actress Patricia Donahue appeared on a number of mystery and western television programs during the 1950's and 1960's, including The Thin Man, Richard Diamond: Private Detective, Peter Gunn, Philip Marlowe, Bat Masterson, Michael Shanye, Bonanza, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, Perry Mason, The Saint, Rod Serling's Night Gallery, The Rockford Files, Barnaby Jones, and an episode of Little House on the Prairie.

"A Stop at Willoughby" remains an enjoyable episode which embodies much of the enduring themes of The Twilight Zone in general and of Rod Serling's writing in particular. Serling and producer Buck Houghton certainly felt that it was one of if not the strongest script produced during the high-quality first season and, like nearly every episode from that inaugural season, "A Stop at Willoughby" is graced by good acting, directing, and a general high quality of production.

Grade: C

Grade: C

Notes:

--Patricia Donahue also appeared in two episodes of Rod Serling's Night Gallery, "The Dear Departed" and "The Hand of Borgus Weems."

--Jason Wingreen also appeared in two episodes of Rod Serling's Night Gallery, "Silent Snow, Secret Snow" and "The Nature of the Enemy."

--Mavis Neal also appeared in an episode of Rod Serling's Night Gallery titled "The Ghost of Sorworth Place."

--Robert Parrish directed two additional episodes of The Twilight Zone, "One for the Angels" and, sharing credit with Alvin Ganzer, "The Mighty Casey," both from season one.

--Jason Wingreen also appeared in two episodes of Rod Serling's Night Gallery, "Silent Snow, Secret Snow" and "The Nature of the Enemy."

--Mavis Neal also appeared in an episode of Rod Serling's Night Gallery titled "The Ghost of Sorworth Place."

--Robert Parrish directed two additional episodes of The Twilight Zone, "One for the Angels" and, sharing credit with Alvin Ganzer, "The Mighty Casey," both from season one.

--Producer Buck Houghton noted in an interview with Marc Scott Zicree, author of The Twilight Zone Companion (second ed., Silman-James, 1989) that the Willoughby sets for the episode were on the MGM back lot and were originally constructed for the Judy Garland musical Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

--As reported by Martin Grams in his book The Twilight Zone: Unlocking the Door to a Television Classic (OTR Publishing, 2008), the made for TV movie For All Time (2000) reuses and revises Serling's script to present a modern retelling of "A Stop at Willoughby."

--"A Stop at Willoughby" was adapted as a Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring Chelcie Ross.

--Rod Serling adapted his teleplay into a short story for More Stories from the Twilight Zone (Bantam, 1961).

--"A Stop at Willoughby" was adapted as a Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring Chelcie Ross.

--Rod Serling adapted his teleplay into a short story for More Stories from the Twilight Zone (Bantam, 1961).

--"A Stop at Willoughy" bears resemblance, almost certainly of a coincidental nature, to a tale from notable ghost story writer A.M. Burrage titled "The Wrong Station," first published in 1916 and later collected in Burrage's 1927 volume Some Ghost Stories. In the tale, a traveler by train is persuaded to exit at the wrong station, upon which he finds himself in an idyllic setting among happy children and adults. He finds a woman to whom he is attracted. The traveled is abruptly pulled away from this situation but returns at story's end after he dies from a heart attack.

--"Willoughby" was the name of the family in the first published ghost story of Henry James, "The Romance of Certain Old Clothes." When James revised the tale for inclusion in his 1885 collection Stories Revived, he changed the family name to Wingrave.

-JP

I give this one an A+! This is one of a handful of episodes that entered my mind and speech and stayed there. Every so often I just blurt out: "Next stop, Willoughby!" I love the direction, especially the dissolve from the swinging lantern. I love the office scenes, especially "Fat boy, why don't you shut your mouth!" And I love the twist ending, the darkness, the snow on the ground...I am totally a fan when it comes to this episode.

ReplyDeleteOh, and before I forget--thanks for the great post! Now I have to go pull out my DVD and watch it again.

Just watched the episode, and it was as good (or better) than I remembered. How great is George T. Clemens? I love both train sets and the floating faces in the bathroom mirror. I love Jason Wingreen as the conductor. And how about this: Willoughby and Son Funeral Home may have been visible from the train as it passed by--maybe Gart saw it and subconsciously wanted to die/escape, so dreamed of Willoughby as the place to go to to get away from his untenable situation. It's also interesting to watch the office scenes as a fan of the current show Mad Men--somehow, I think the TZ office is much more like reality in 1960.

ReplyDeleteHey, Jack, I can dig it! The wonderful nature of the show is that it works on so many levels and effects different viewers in various ways. I must admit that I tend to prefer the Zone's darker fare and perhaps have a disposition to lean that way in grading. I think the direction and the dialogue are the two strongest aspects of the episode, though the acting is equally strong. We always appreciate your comments so stay tuned and thanks for reading.

ReplyDeleteThough I failed to mention it you are absolutely right about the Mad Men connection. Serling was way ahead of his time in portraying the grind of the bussinessman, especially in the advertising business, from "Patterns" and "Walking Distance" up to "A Stop at Willoughby."

ReplyDeleteThis is one of my favorite episodes. I would also give it A+ !!

ReplyDeleteI had a commute past the Willoughby on the metro north. More than once did I wonder about stepping off to wander about. Hehe.

ReplyDeleteI worked in advertising to boot! Although it was a reverse commute, and not into the city for work. :)

He did not "step" off the train at his final Willoughby stop. He JUMPED. I think that fact makes it more curious as to if he wanted to die. Because when he was sleeping the times before , the train stopped and he walked off. Any thoughts?

ReplyDeleteI think he only stepped off the train the last time in his dream, so that's what led to his actual death.

DeleteI can relate to this early episode of TZ in a number of ways. My dad worked in NYC and took the train 5 days a week for over 35 years and the stops the conductor called out were on the New Haven line. Rod Serling lived in Westport, CT at the time. Ad agencies I presume haven't changed much in all of those years and the same with suburbia in Westport, CT where the fictional Garth lived with his trophy wife. Garth was under tremendous stress at work and was compounded with his cold and domineering wife. He invented Willoughby in his mind of course, and ended up as his final resting spot, Willougby. We would all like the ability to go back to a more simpler time, but I would not choose the 1880's due to poor medical care and no air-conditioning or electricity. I would choose the late 50's or early 60's. I have joked with conductors on Metro North (same line as the episode) asking them to wake me up when we get near Willoughby who were on the older side (in their 60's) and one or two of them took awhile but got the joke and cracked a smile! I guess they heard it before. The episode with Robert Duvall in "Miniature" is a similar theme and one of my favorites in the subject of morphing oneself into a fantasy world, however; unlike Garth Williams in Willoughby, the character, Charlie, in the episode "Miniature" did not die but got to live his dream with the love of his life :OD.

ReplyDeleteIt's a metaphor for suicide.

ReplyDeleteWow, a C? I’ll have to respectfully disagree with that grade. What really pushes it over the top for me is the fact that Gart got what he wanted in the end and that made me happy. Same way I felt about Arthur Curtis.

ReplyDeleteI really enjoy the site. Great reading

Hey, thanks for reading! Yeah, this one is certainly the episode our readers most ardently disagree with our critique. I suppose it's just one of those episodes which never worked for me, although I appreciate its place as a favorite among fans.

DeleteIn North Conway, New Hampshire, in the sidewalk on the street in front of the old-fashioned railway station, there are blocks set in memoriam of deceased local residents. Some were put there by their families, others in accordance with the wishes of the individuals themselves. One day, while on my annual vacation visit to New Hampshire, I was walking down the street, happened to look down at exactly the right moment, and saw the words "NEXT STOP, WILLOUGHBY" looking back at me. It's amazing how Rod Serling's impact on the culture can make itself felt in the least-expected places. (In retrospect, things could certainly have been a LOT worse. Would I have ever gotten a good night's sleep again if I'd been greeted with: "YOU'RE A BAD MAN! YOU'RE A VERY BAD MAN!" or "MY NAME IS TALKY TINA, AND YOU'D BETTER BE NICE TO ME!")?

ReplyDeleteIn case there's anybody from the North Conway area who's read my little post above, I should mention that I looked at my camera archive, where I have a snapshot of the stone tablet that I described. It reads: "IN LOVING MEMORY OF BONNIE WEINSTEIN", right above the Willoughby reference. If there's anyone out there who can shed any light on the late Ms. Weinstein and her affinity for the world of the "Twilight Zone", I'd love to hear from you.

ReplyDeleteI always thought that the reason the hearse with the sign "Willoughby and Son" is shown at the end is to suggest that Gart saw that sign at some point and the name stuck with him, which is how his subconscious mind created his fantasy. Subconsciously, he was really longing for death.

ReplyDelete