|

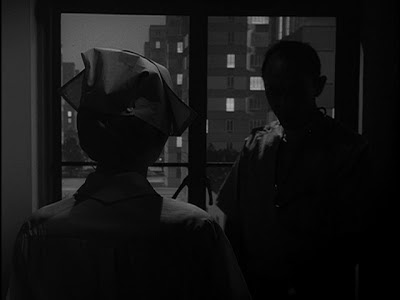

| The face of Miss Janet Tyler, patient in room 307 |

Season Two, Episode 42

Original Air Date: November 11, 1960

Janet Tyler (under bandages): Maxine Stuart

Janet Tyler (revealed): Donna Douglas

Doctor: William D. Gordon

Janet’s Nurse: Jennifer Howard

Walter Smith: Edson Stroll

Nurse #2: Joanna Heyes

Leader: George Keymas

Writer: Rod Serling (original teleplay)

Director: Douglas Heyes

Producer: Buck Houghton

Associate Producer: Del Reisman

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson and Darrell Hallenbeck

Associate Producer: Del Reisman

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson and Darrell Hallenbeck

Director of Photography: George T. Clemens

Art Direction: George W. Davis and Philip Barber

Set Decoration: Henry Grace and H. Web Arrowsmith

Assistant Director: Henry Weinberger

Casting: Ethel Winant

Editor: Leon Barsha

Sound: Franklin Milton and Charles Scheid

Art Direction: George W. Davis and Philip Barber

Set Decoration: Henry Grace and H. Web Arrowsmith

Assistant Director: Henry Weinberger

Casting: Ethel Winant

Editor: Leon Barsha

Sound: Franklin Milton and Charles Scheid

Music: Bernard Hermann

Makeup: William Tuttle

And Now, Mr. Serling:

“Next week you’ll see these bandages unwrapped. And you’ll get a good, close look at the face beneath them. It’s an excursion into the odd and into the very, very different. Our play is called “The Eyes of the Beholder” and it comes recommended. I hope we’ll see you next week on The Twilight Zone. Thank you, and goodnight."

Rod Serling’s Opening Narration:

“Suspended in time and space for a moment, your introduction to Miss Janet Tyler, who lives in a very private world of darkness, a universe whose dimensions are the size, thickness, length of a swath of bandages that cover her face. In a moment we’ll go back into this room and also in a moment we’ll look under those bandages, keeping in mind, of course, that we’re not to be surprised by what we see, because this isn’t just a hospital, and this patient, 307, is not just a woman. This happens to be the Twilight Zone, and Miss Janet Tyler, with you, is about to enter it."

Summary:

Miss Janet Tyler sits alone in a shadow-draped hospital room staring off into the black nothingness that has become her existence. Miss Tyler has not left her hospital room in what seems like a lifetime. She hasn’t seen a blade of grass, felt the afternoon sun upon her skin, or stared up into a night sky filled with stars in so long that she has practically forgotten that all of these things are possible. Layers of thick bandages cover her face, keeping her isolated in her own private world of darkness.

In a moment the secret of her torment is revealed: Miss Tyler was born with a severely disfigured face and has been placed in the state-run hospital in hopes of having massive reconstructive surgery. As a result of the procedure Miss Tyler’s face will remain under the bandages until the end of the story and as for the hospital staff, their likenesses will also remain a mystery. Their faces will remain cloaked in shadows or hidden behind various objects and will be revealed at the same time as Miss Tyler’s.

Miss Tyler desperately desires a solution to her problem. This is her eleventh treatment, the maximum number allowed by the state. If it proves a failure then she will be sent to a state-mandated segregation camp for people with similar deformities. She tells the doctor that if the treatment has failed again then she wants to be exterminated. She does not desire to live in a segregation camp. The doctor informs her that while this practice is not totally unheard of he doubts that her request will be granted.

Miss Tyler’s doctor is not unsympathetic to her dilemma. He finds himself torn between being a law-abiding citizen of the state and a humanitarian of science. While talking with Miss Tyler’s nurse he says that he simply doesn’t understand why a person who looks different must live in isolation and alienation. The nurse warns him that his words sound dangerously like treason.

Back in room 307, Miss Tyler pleads for the bandages to be removed. The doctor finally agrees to remove them. Layer by layer, the bandages are lifted. As the final layer is removed screams fill the room. Underneath the bandages is a young woman with full head of blonde hair, penetrating eyes, and a soft face. We get a glimpse of the hospital staff: they all have grotesque pig-like faces with snarling snouts and deep, sunken eyes. Miss Tyler needs no mirror to understand her situation. The operation has failed. She panics. She jumps out of her chair and runs screaming down the hallway. On large television monitors placed throughout the hospital a fiery political figure referred to as “The Leader” speaks of a superior race that can only function properly if everyone is made of the same formula.

Miss Tyler runs into a room and finds a man waiting there. He lacks the snout and the sunken, dead eyes that the rest of the hospital staff possess. Instead he looks more like her. She recoils in horror and with nowhere left to go, sinks down into a corner and covers her eyes. The doctor enters the room. He informs Miss Tyler that the man’s name is Walter and he is a representative of the segregation camp where she is going to live. Walter tells her that she no longer needs to be ashamed of her appearance, no longer needs to hide her face from the rest of the world. Where she is going there will be people who look just as she does. He takes her hands and gently leads her out of the room. She begins to relax and the two of them stroll, hand in hand, slowly down the hallway, past the crowd of onlookers, toward a new beginning.

Rod Serling’s Closing Narration:

“Now the questions that come to mind. Where is this place and when is it? What kind of a world where ugliness is the norm and beauty the deviation from that norm? You want an answer? The answer is: it doesn’t make any difference. Because the old saying happens to be true. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. In this year or a hundred years hence, on this planet or wherever there is human life, perhaps out among the stars, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Lesson to be learned…in The Twilight Zone."

Commentary:

Following on the heels of Charles Beaumont's “The Howling Man,” The Twilight Zone continued its incredible creative streak with Rod Serling’s “Eye of the Beholder.” One of the most widely recognized episodes of the series, “Eye of the Beholder” is the signature episode of director Douglas Heyes and makeup artist William Tuttle. There is not a missed note in the entire episode and every aspect of it is of the highest possible quality that the show had to offer.

Following on the heels of Charles Beaumont's “The Howling Man,” The Twilight Zone continued its incredible creative streak with Rod Serling’s “Eye of the Beholder.” One of the most widely recognized episodes of the series, “Eye of the Beholder” is the signature episode of director Douglas Heyes and makeup artist William Tuttle. There is not a missed note in the entire episode and every aspect of it is of the highest possible quality that the show had to offer.

When Buck Houghton first received this script he was reportedly terrified at trying to pull off a twenty-four minute episode where the audience does not get to see any of the character’s faces until the very end. His first choice to direct such an arduously technical episode was Douglas Heyes. In order to keep the viewers from immediately suspecting that something is wrong (i.e. “Hey, why aren’t they showing anyone’s face?”) Heyes keeps the action constantly moving, not in a frenetic way but there is always motion of either the actors or the camera. For instance, in the scene where the doctor walks from the shadows into the light and begins to look directly at the camera his face is briefly hidden behind a nurse, who is standing right in front of him at precisely the right moment, before he turns his back to the audience. The dark and shadowy atmosphere of the set played a large role in hiding the character’s faces. In other episodes this may seem like an intrusion that the audience would pick up on immediately but as this story exists in a world not of our own, the dark, grim set doesn’t seem entirely out of place. The audience doesn’t notice the character’s images being withheld from them because for a large chunk of the episode the camera is centered on Janet Tyler. The sequence of the unveiling is particularly impressive as it is shot from Tyler’s point of view so the audience gets to experience the bandages being lifted, layer by layer, from her face. To accomplish this Heyes had director of photography George T. Clemens place the camera inside a fish tank and had the bandages wrapped tightly around the outside of the tank. It’s an unusual technique and an effective one.

As much as "Eye of the Beholder" depended upon effective portrayal of character by the actors and the filming ingenuity of director Douglas Heyes and photographer George Clemens, so too did the makeup play a crucial role in the believably and effectiveness of the episode. Makeup artist William Tuttle, then head of the MGM makeup department and the show's go-to technician, rose to the challenge and delivered arguably the show's most recognizable makeup effect.

For The Twilight Zone, Tuttle was typically asked to create a single makeup ("Nightmare at 20,000 Feet, “ "Hocus Pocus and Frisby") or a handful of effects ("The After Hours," "The Masks") but for "Eye of the Beholder" Tuttle was faced with having to apply his grotesque makeup design on a dozen actors or actresses. Though time was not a problem, production manager Ralph W. Nelson was able to secure a longer preparation time for "Eye of the Beholder," expense would become an issue during the initial stages of developing the makeup. Director Douglas Heyes immediately recognized this problem and approached Tuttle about developing a more streamlined, and thus more cost efficient, method of achieving the makeup effects. Tuttle's typical method of developing his makeup was to take a plaster cast of the all the actors’ faces upon which the makeup would need to be applied. This is a highly efficient way to develop a makeup which perfectly fits the features of individual actors’ faces and is most often used to create a unique makeup which can be molded to the needs and capabilities of the show and the actors. Tuttle would use this method to great effect four years later, working with director George Pal, writer Charles Beaumont, and actor Tony Randall, for 7 Faces of Dr. Lao, for which he would win a special Academy Award (an annual Academy Award for special effects makeup, under the umbrella of "Best Makeup and Hairstyling" would not come into existence until 1981). Fortunately, such an individualized method for the makeup design would not be needed for "Eye of the Beholder" since the purpose of the method, and the theme of the entire episode, was uniformity. Still, Heyes wanted the actors’ natural features to somewhat show through the makeup and also for the actors to be able to perform comfortably through the makeup once their appearances are revealed onscreen and spoken dialogue is required.

The solution was found in foam rubber latex appliances which could be applied to the actors’ faces in a uniform manner. Forming a cast of each of the twelve actors’ faces was out of the question and Tuttle only formed three casts upon which to mold the appliances. Upon careful observation these three designs can be seen in the final cut of the episode to be two "male" models and one "female" model, though at one point in the show an actress is seen to be wearing a "male" model of the makeup, undoubtedly to distort the perception of the viewer, something director Heyes and photographer George Clemens were constantly trying to do on "Eye of the Beholder."

Heyes had experience with art direction and animation prior to his career as a director and worked hands on in developing the makeup effects alongside Tuttle, on both a design and crafting level. Tuttle had recently created the terrifying Morlocks for George Pal's The Time Machine (1960) and a lot of that makeup design made it into "Eye of the Beholder." It was Heyes who suggested that Tuttle use the leftover appliances from The Time Machine to develop something similar for the grotesque effects needed for "Eye of the Beholder." The differences in the two "male" models of the makeup are two-fold. The first is the brow piece. The first model, the one worn by William Gordon as the Doctor, included a much accentuated brow piece, applied thinly at the hairline and gaining thickness above the eyes, creating a jutting bone structure above the eyebrows. The second design, worn by the male nurses, did not feature as pronounced a brow. One nostril on each of the pig-shaped noses applied to the actors flared chiefly in one direction. This varied between the two "male" designs. The "female" design was more streamlined with a more upturned nose that did not extended out from the face as much as the counterpart designs and featured virtually no brow piece though two layers of makeup, for consistency, can be discerned on the foreheads of the actresses.

Tuttle had previous experience in creating a makeup intended to unify a design while working under former MGM head of makeup Jack Dawn. Dawn's most memorable makeup was featured in MGM's 1939 Technicolor musical The Wizard of Oz. That film featured several grotesque makeups, some with a unifying theme. Dawn was also an innovator in crafting appliance makeup pieces, no doubt from his experience on The Wizard of Oz, a film plagued by problems in cost and time.

The final interesting aspect of the makeup was that actress Maxine Stuart, Janet Tyler under the bandages, recalls having a plaster cast made of her face. This was used to create a gauze bandage appliance that could be slipped over Stuart's face like a mask instead of wrapping the actress anew each day of shooting. Not only would the latter method be time consuming and very uncomfortable for the actress but would also lend itself to an aesthetic inconsistency. Tuttle crafted a foam rubber mask from the mold of Stuart's face which would then be wrapped in gauze for ease of application. Stuart’s chin and neck were wrapped in gauze each day of shooting since they were not covered by the appliance. When watching the episode, the viewer can easily see where the appliance ends above Stuart's chin.

In all, the makeup for "Eye of the Beholder" was one of the most challenging yet rewarding and successful in the entire run of the show. The makeup has been re-imagined by artists and sculptors for posters, prints, magazines, toys, and figures in a seemingly endless stream since the original airing of the episode and has undoubtedly become one those indelible images which has lived on as an identifying factor in The Twilight Zone's cultural heritage.

In addition to the technical challenges that this episode offered, Douglas Heyes also knew that the story would be carried largely by the voices of the actors because it is all the audience has with which to associate themselves. As he told Marc Scott Zicree, author of The Twilight Zone Companion (1982), to cast this episode he had the actors audition with his back to them so that he would hear what the audience would hear. He felt that the voices should be sympathetic both to sway the audience from deciphering the twist but also so that they would form an emotional connection to the characters. In contrast, he felt that Miss Tyler's voice should be fairly coarse and textured, one that displayed a depth of character. The result of this unusual casting process was a stellar cast with a leading lady that basically carried most of the episode herself. A former radio actress, Maxine Stuart’s performance here is exceptional considering she must make the audience sympathize with Janet Tyler without using any facial expressions. This was an enormous responsibility because the story hinges on how much the audience cares for Tyler, how much they want to see the treatment turn out a successful one. If they do not sympathize with her then the entire episode falls apart. Stuart accomplishes this brilliantly with simple voice intonations and hand gestures, remaining melancholy but hopeful for most of her performance but exploding into a helpless rage when the script calls for it. Equally as important to Stuart’s performance as Janet Tyler is that of the Doctor played William D. Gordon. Since the Doctor is emotionally torn between his humanitarianism and his obligation as a state employee this has to be reflected in the actor’s voice. Gordon accomplishes this convincingly and the scene in which he discusses his thoughts with the head nurse is one of the most poignant in the episode.

The final major cast member of the episode is Donna Douglas who portrays Janet Tyler after the bandages have been removed. While Maxine Stuart was an ideal choice to voice the faceless Tyler, the producers felt that Janet Tyler should be breathtakingly beautiful in comparison to the grotesque image of the pig people. Stuart plays Tyler up until the removal of the bandages but once they are taken off Douglas takes over as Tyler for the remainder of the episode. Douglas has only a few lines after the bandages have been removed. There are contradictory accounts as to whose voice is heard when Douglas speaks. Stuart recorded a voiceover to sync her voice to Douglas’s facial movements so that the audience would not suspect that two different actresses were playing the same role. According to Stuart it is her voice that is used in the final cut of the episode. Heyes and Douglas, however, both contest that Douglas was on the set during the entire production and learned Stuart’s intonations well enough to recite her few lines believably and that it is her voice that is heard in the last scene of the episode. Either way both performances are convincing and important to the story.

For those who have seen this episode in syndication you might have seen the version entitled “The Private World of Darkness.” Serling’s original title was “Eye of the Beholder” and its meaning was the basic moral lesson to be taken from the story. When it first aired on CBS on November 11, 1960 it ran under this title. Shortly after, however, Serling and Cayuga Productions received a letter from Stuart Reynolds, a television producer for General Electric Theater which ran on CBS from 1953 to 1962, stating that in October of 1953 General Electric Theater aired an episode written by Hannah Grad Goodman titled “The Eye of the Beholder.” Reynolds was now trying to market this production as an educational film to be used in schools and in a roundabout way he threatened to sue Serling if he did not change the name of his Twilight Zone episode. Not wanting to pick an unneeded fight Serling and the producers decided to change to the name. When the episode was next broadcast in 1962 it bore the name “The Private World of Darkness.” Since then it has been released commercially under both names but usually the syndicated version runs under the title “The Private World of Darkness” simply because when it first aired in syndication it bore this name. Regardless, most people know it under the name that Serling originally intended.

As mentioned this is one of the signature episodes of the series. Whenever there is a reference to The Twilight Zone this is one of a handful of episodes that is mentioned. As for the filmmakers, both Rod Serling and Douglas Heyes both consider this one of their best efforts on the program. Serling would later recycle this same theme on Night Gallery in the episode “The Different Ones” where a deformed teenage boy is sent by a totalitarian society concerned with conformity to live on another planet. When he arrives he discovers that it is to be an exchange as a creature from this new planet, a seemingly attractive human man, is being sent to Earth. To the teenager’s surprise the people from his new home look much like he does and all is well. It was also remade almost verbatim for the UPN revival series in 2003. The producers of this series choose not to change anything and both the concept and script and many of the camera shots are duplicated as well as they can be. The end product is simply a diluted version of the original. This episode has also been spoofed on Saturday Night Live and The Simpsons and many other programs. Serling hit upon a theme here that is often spoken of but rarely put into images as clearly as this episode. And thanks to remarkable casting, Douglas Heyes’s painstakingly choreographed camera work, and William Tuttle’s uniquely grotesque artistry, this episode is still a very recognizable stamp on the face of American popular culture.

Grade: A+

Grateful acknowledgment is made to:

The Twilight Zone Companion, Second Edition by Marc Scott Zicree (Silman-James Press, 1992)

The Twilight Zone: Unlocking the Door to a Television Classic by Martin Grams, Jr. (OTR Publishing, 2008)

"Douglas Heyes: Behind the Scenes at The Twilight Zone" by Ben Herndon. Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine (August, 1982)

Grateful acknowledgment is made to:

The Twilight Zone Companion, Second Edition by Marc Scott Zicree (Silman-James Press, 1992)

The Twilight Zone: Unlocking the Door to a Television Classic by Martin Grams, Jr. (OTR Publishing, 2008)

"Douglas Heyes: Behind the Scenes at The Twilight Zone" by Ben Herndon. Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine (August, 1982)

|

Original design sketch by director Douglas Heyes

for makeup applied to actor William Gordon

featured in an interview with Heyes in the

Aug, 1982 issue of Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone Magazine

|

--William D. Gordon also appeared in an earlier Season Two episode “Nervous Man in a Four Dollar Room” which was also written by Serling and directed by Douglas Heyes.

--Douglas Heyes was the director responsible for some of the most memorable episodes of the series, including "The After Hours," "The Howling Man" and "The Invaders." Heyes wrote and directed the first segment of Rod Serling's Night Gallery, "The Dead Man" (based on the story by Fritz Leiber), and wrote two additional segments, "The Housekeeper" and "Brenda" (based on the story by Margaret St. Clair) under the pseudonym Matthew Howard. Soon after the broadcast of "Eye of the Beholder," Heyes would re-team with actress Donna Douglas for "The Hungry Glass," a classic episode of Boris Karloff's Thriller, which originally aired on January 3, 1961. "The Hungry Glass" was an episode loaded with Zone actors/actresses and also featured William Shatner ("Nick of Time," "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet"), Russell Johnson ("Execution," "Back There"), Elizabeth Allen ("The After Hours"), and Clem Bevans ("Hocus-Pocus and Frisby"). "The Hungry Glass" also starred Heyes's wife Joanna Heyes, who here plays the receptionist nurse under William Tuttle's makeup. Douglas Heyes directed two additional episodes of Thriller, including the excellent first season episode "The Purple Room," which featured Patricia Barry ("The Chaser," "I Dream of Genie," and "It's a Good Life" segment from Twilight Zone: The Movie).

--George Keymas also appeared in an episode of Rod Serling's Night Gallery titled "Green Fingers."

--Donna Douglas also appeared in an episode of Rod Serling's Night Gallery titled "Last Rites for a Dead Druid."

--Edson Stroll also appeared in season three's "The Trade-Ins."

--"Eye of the Beholder" was adapted as a Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring Virginia Williams.

--While this episode looks remarkable in high definition in many ways the high resolution may not do it justice as there are several scenes in which the actors faces can be seen quite clearly wearing no makeup.

Up Next: Another masterpiece from the best television program of all time, this one written by Richard Matheson. Join us next time when we review “Nick of Time,” starring William Shatner.

--JP and BD