“Perchance to Dream”

Season One, Episode 9

Original Air Date: November 27, 1959

Season One, Episode 9

Original Air Date: November 27, 1959

Cast:

Edward Hall: Richard Conte

Dr. Eliot Rathmann: John Larch

Maya the Catgirl/Miss Thomas: Suzanne Lloyd

Edward Hall: Richard Conte

Dr. Eliot Rathmann: John Larch

Maya the Catgirl/Miss Thomas: Suzanne Lloyd

Crew:

Writer: Charles Beaumont (from his short story)

Director: Robert Florey

Producer: Buck Houghton

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson

Director of Photography: George T. Clemens

Art Direction: George W. Davis and William Ferrari

Set Decoration: Rudy Butler and Henry Grace

Assistant Director: Edward Denault

Casting: Mildred Gusse

Editor: Joseph Gluck

Sound: Franklin Milton and Philip Mitchell

Music: Nathan Van Cleave

Writer: Charles Beaumont (from his short story)

Director: Robert Florey

Producer: Buck Houghton

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson

Director of Photography: George T. Clemens

Art Direction: George W. Davis and William Ferrari

Set Decoration: Rudy Butler and Henry Grace

Assistant Director: Edward Denault

Casting: Mildred Gusse

Editor: Joseph Gluck

Sound: Franklin Milton and Philip Mitchell

Music: Nathan Van Cleave

And Now, Mr. Serling:

"Next week we enlist the considerable literary talents of Mr. Charles Beaumont and invite you to join us in a strange and shocking dream. Our story is called 'Perchance to Dream' and stars Richard Conte. I hope you'll be able to join next week's excursion into the Twilight Zone. Thank you and good night."

"Next week we enlist the considerable literary talents of Mr. Charles Beaumont and invite you to join us in a strange and shocking dream. Our story is called 'Perchance to Dream' and stars Richard Conte. I hope you'll be able to join next week's excursion into the Twilight Zone. Thank you and good night."

Rod Serling's Opening Narration:

"Twelve o'clock noon. An ordinary scene, an ordinary city. Lunch time for thousands of ordinary people. To most of them, this hour will be a rest, a pleasant break in the day's routine. To most, but not all. To Edward Hall time is an enemy, and the hour to come is a matter of life and death."

"Twelve o'clock noon. An ordinary scene, an ordinary city. Lunch time for thousands of ordinary people. To most of them, this hour will be a rest, a pleasant break in the day's routine. To most, but not all. To Edward Hall time is an enemy, and the hour to come is a matter of life and death."

Summary:

Edward Hall has been awake for four days and four nights. Diagnosed at a young age with a degenerative heart condition, he is afraid to fall asleep for fear that the climax of a recurring nightmare will provide shock enough to stop his heart. He seeks the help of a psychiatrist, Dr. Eliot Rathmann, to whom he tells his story. Walking into Rathmann's office, Hall nearly collapses on his feet. Rathmann urges Hall to lie down but, after only a moment on the psychiatrist's couch, Hall jumps up, needing to pace the room to stay awake.

Hall opens a window. Fearing his patient may be suicidal, Rathmann moves Hall away and closes the window. This strikes Hall as funny because, as he tells the doctor, he wishes to live and that is his problem. Hall explains that he is prone to an over-active imagination, able to convince himself of things that he knows, intellectually, are not true but still able to feel the repercussions of his imaginative exploits. His imagination dwells on dark and morbid subjects. Reading of a woman victimized by a man hiding in the backseat of her car, Hall imagines such a murderer hiding in the back of his car, causing him to wreck on Laurel Canyon. Luckily, he made it out alive.

Hall continues by documenting his recurring nightmare. It involves a frighteningly off-kilter amusement park where he is drawn to a deadly and alluring stage performer named Maya the Cat Girl. In his dream, Hall runs from the stage as Maya performs her seductive dance only to find, moments later, that Maya has followed him, determined to hang on Hall's arm and have him take her around the amusement park.

Pulling Hall into a twisted, terrifying funhouse, Maya seems to take sadistic pleasure in Hall's rising panic and, though Hall is fully aware that he is dreaming, he explains again and again that his heart cannot take shock or high excitement.

Compelled by Maya against his better judgment to board a roller coaster, Hall panics as the ride rises higher and gains speed. He screams that he can't take it anymore and must get out. Maya, laughing maniacally, urges Hall to jump from the roller coaster. This is the moment from which Hall last awakened.

In Rathmann's office, he tells the doctor that were he to sleep again he would find himself back on that roller coaster, sure that Maya would push him from the ride as it rose to its highest point. On the other hand, were he to stay awake much longer, the strain would be too much for his heart and that would kill him. As Hall puts it: "Heads you win, tails I lose."

His story told, Hall decides that Dr. Rathmann can do nothing more for him and, against the doctor's advice, leaves the office. In the waiting area he sees Dr. Rathmann's receptionist. It's Maya the Cat Girl! Shocked and stunned, Hall retreats back into the doctor's office. After telling the doctor that his receptionist is Hall's would-be murderer, Hall runs across the room and leaps through a window to plummet several stories to his death.

We then see Hall lying peacefully on the psychiatrist's couch, eyes closed. Dr. Rathmann takes Hall's wrist in his hand to feel for his pulse and gets nothing. He calls his receptionist, Miss Thomas, into the office and she is, in fact, the prosaic image of Maya the Cat Girl. Rathmann tells her that Hall came in, laid down and, in two seconds, was asleep, only to let out one final scream and die from a probable heart attack. As the doctor ironically says: "At least he died peacefully"!

Edward Hall has been awake for four days and four nights. Diagnosed at a young age with a degenerative heart condition, he is afraid to fall asleep for fear that the climax of a recurring nightmare will provide shock enough to stop his heart. He seeks the help of a psychiatrist, Dr. Eliot Rathmann, to whom he tells his story. Walking into Rathmann's office, Hall nearly collapses on his feet. Rathmann urges Hall to lie down but, after only a moment on the psychiatrist's couch, Hall jumps up, needing to pace the room to stay awake.

Hall opens a window. Fearing his patient may be suicidal, Rathmann moves Hall away and closes the window. This strikes Hall as funny because, as he tells the doctor, he wishes to live and that is his problem. Hall explains that he is prone to an over-active imagination, able to convince himself of things that he knows, intellectually, are not true but still able to feel the repercussions of his imaginative exploits. His imagination dwells on dark and morbid subjects. Reading of a woman victimized by a man hiding in the backseat of her car, Hall imagines such a murderer hiding in the back of his car, causing him to wreck on Laurel Canyon. Luckily, he made it out alive.

Hall continues by documenting his recurring nightmare. It involves a frighteningly off-kilter amusement park where he is drawn to a deadly and alluring stage performer named Maya the Cat Girl. In his dream, Hall runs from the stage as Maya performs her seductive dance only to find, moments later, that Maya has followed him, determined to hang on Hall's arm and have him take her around the amusement park.

Pulling Hall into a twisted, terrifying funhouse, Maya seems to take sadistic pleasure in Hall's rising panic and, though Hall is fully aware that he is dreaming, he explains again and again that his heart cannot take shock or high excitement.

Compelled by Maya against his better judgment to board a roller coaster, Hall panics as the ride rises higher and gains speed. He screams that he can't take it anymore and must get out. Maya, laughing maniacally, urges Hall to jump from the roller coaster. This is the moment from which Hall last awakened.

In Rathmann's office, he tells the doctor that were he to sleep again he would find himself back on that roller coaster, sure that Maya would push him from the ride as it rose to its highest point. On the other hand, were he to stay awake much longer, the strain would be too much for his heart and that would kill him. As Hall puts it: "Heads you win, tails I lose."

His story told, Hall decides that Dr. Rathmann can do nothing more for him and, against the doctor's advice, leaves the office. In the waiting area he sees Dr. Rathmann's receptionist. It's Maya the Cat Girl! Shocked and stunned, Hall retreats back into the doctor's office. After telling the doctor that his receptionist is Hall's would-be murderer, Hall runs across the room and leaps through a window to plummet several stories to his death.

We then see Hall lying peacefully on the psychiatrist's couch, eyes closed. Dr. Rathmann takes Hall's wrist in his hand to feel for his pulse and gets nothing. He calls his receptionist, Miss Thomas, into the office and she is, in fact, the prosaic image of Maya the Cat Girl. Rathmann tells her that Hall came in, laid down and, in two seconds, was asleep, only to let out one final scream and die from a probable heart attack. As the doctor ironically says: "At least he died peacefully"!

Rod Serling's Closing Narration:

"They say a dream takes only a second or so and yet in that second a man can live a lifetime. He can suffer and die and who's to say which is the greater reality, the one we know or the one in dreams, between heaven, the sky, the earth, in the Twilight Zone."

"They say a dream takes only a second or so and yet in that second a man can live a lifetime. He can suffer and die and who's to say which is the greater reality, the one we know or the one in dreams, between heaven, the sky, the earth, in the Twilight Zone."

Commentary:

In 1962, three years after "Perchance to Dream" aired during the first season of The Twilight Zone, Charles Beaumont edited an anthology of horror stories for Ballantine Books, titled The Fiend in You. Outside of functioning as a showcase for the fantasy writers directly and tangentially related to a writers group centered around Beaumont in southern California, with stories by Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, William F. Nolan, Henry Slesar, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and Charles E. Fritch, among others, the anthology aimed to essentially bury the traditional tropes of the horror genre. In his introduction to the book Beaumont wrote:

In 1962, three years after "Perchance to Dream" aired during the first season of The Twilight Zone, Charles Beaumont edited an anthology of horror stories for Ballantine Books, titled The Fiend in You. Outside of functioning as a showcase for the fantasy writers directly and tangentially related to a writers group centered around Beaumont in southern California, with stories by Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, William F. Nolan, Henry Slesar, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and Charles E. Fritch, among others, the anthology aimed to essentially bury the traditional tropes of the horror genre. In his introduction to the book Beaumont wrote:

In 1962, three years after "Perchance to Dream" aired during the first season of The Twilight Zone, Charles Beaumont edited an anthology of horror stories for Ballantine Books, titled The Fiend in You. Outside of functioning as a showcase for the fantasy writers directly and tangentially related to a writers group centered around Beaumont in southern California, with stories by Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, William F. Nolan, Henry Slesar, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and Charles E. Fritch, among others, the anthology aimed to essentially bury the traditional tropes of the horror genre. In his introduction to the book Beaumont wrote:

In 1962, three years after "Perchance to Dream" aired during the first season of The Twilight Zone, Charles Beaumont edited an anthology of horror stories for Ballantine Books, titled The Fiend in You. Outside of functioning as a showcase for the fantasy writers directly and tangentially related to a writers group centered around Beaumont in southern California, with stories by Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, William F. Nolan, Henry Slesar, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and Charles E. Fritch, among others, the anthology aimed to essentially bury the traditional tropes of the horror genre. In his introduction to the book Beaumont wrote: "Sad, but true: after centuries of outstanding service to the human imagination, the classic terrors - the ghosts, the vampires, the werewolves, the witches, the goblins, all the things that go bump in the night - have suddenly found themselves unable to get work, except as comedians. We love them, of course. And we feel sorry for them. But we are not afraid of them any more."

This could also serve as the mission statement for The Twilight Zone, a series which generally avoided traditional figures in horror, with the notable exceptions of the ever-pliable ghost and the Devil. The latter figure was, with the exception of Beaumont's "The Howling Man," repeatedly used in a humorous manner. In The Twilight Zone, memory, dreams, existence, perspective, superstition, and the shimmering gloss of reality provided the stages for terror and transition.

Likewise, in The Fiend in You, Beaumont essentially rang the funeral bell for the outside terrors, proclaiming instead that the emerging horrors of the late twentieth century were to be found in the human mind. These are the terrors of the psychiatrist's couch. It is only fitting, then, that the story Beaumont included from his own work was "Perchance to Dream," first published in the October, 1958 issue of Playboy. In his introduction to the story, Beaumont wrote:

"When I wrote 'Perchance to Dream,' I didn't have any idea of its genesis. Only much later did I remember the woman at the amusement park, sitting all by herself in the whirling 'Whip,' eyes closed, smiling; and the tapestry at which I'd stared in ten-year-old awe, waiting for the horses to move ('They will if you look at them long enough!); and the first time I'd wondered how it would feel to plunge forty stories to the hard cement below . . . From all of these real impressions, the following 'unreal' story was woven."

Charles Beaumont is credited with more episodes (22) of The Twilight Zone than any writer except series creator Rod Serling (92). Almost every episode he wrote was of high quality and a few are outright classics. His first offering is among his best. As Rod Serling was writing scripts tackling varied subjects and attempting to find a consistent thematic identity for the first season, Beaumont arrived on the series fully formed with a penchant for dark fantasy subjects, a distinctive style, and his own thematic concerns. For Beaumont, the idea of dreams and nightmares, the functionality of illusion and imagination, were utmost concerns in his fictional output. Although he had previous television writing credits to his name, Beaumont was encouraged by Rod Serling to adapt the short story exactly as written, not to change any elements in an attempt to cater to the perceived confines of the television medium. As Beaumont stated in "The Seeing I," a column of television commentary he wrote for the December, 1959 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction:

"Serling told me to dramatize it but to make no changes. He advised me to forget everything I'd learned about television taboos. They didn't exist on The Twilight Zone."

Beaumont supplied a tightly written, thematically rich script, car crashes, roller coasters, and all. "It was filmed exactly as written," Beaumont wrote. "I know because I was on the set, watching, unable to believe that any of it was truly happening. I'd done over thirty teleplays and seen them spoiled by the hundred-handed companies. But it was happening. An author was seeing his work treated with respect."

"Perchance to Dream" was a production blessed with all the right people in all the right places. Complementing Beaumont's tersely written psychological horror story were a group of dramatists perfectly suited to bringing the writer's vision to life. The small cast included three excellent performers, with Richard Conte giving an especially nerve-racking performance as the doomed Edward Hall. Twilight Zone regular John Larch (who later appeared on the series in "Dust" and "It's a Good Life") brings his usual subtle acting style to bear upon an often stereotyped character and lends the manic story a sense of calm and intelligence. Canadian actress Suzanne Lloyd perfectly captures the duality of Maya the Cat Girl, that of the alluring and the frightening.

Director Robert Florey was no stranger to the tropes of surrealistic horror, having co-scripted Universal Studio's 1931 production of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, directed by James Whale (initially slated for Florey to direct), as well as having adapted and directed Edgar Allan Poe's Murders in the Rue Morgue starring Bela Lugosi the following year. Florey is also known for directing the 1946 film The Beast With Five Fingers in which Peter Lorre is terrorized by a disembodied hand. That film was based on a short story by W.H. Harvey. Florey does a marvelous job on "Perchance to Dream," lending the episode's hallucinatory set design and dream-like action and imagery a verisimilitude that manages to keep the viewer's attention hooked along the line of the episode's breakneck pacing. As Beaumont wrote, Florey "rooted out the meaning of certain lines, frequently surprising me with symbols and shadings I'd neither planned nor suspected. The set was truly impressionistic, recalling the days of 'Caligari' and 'Liliom.'" Florey was highly influenced by German Expressionism and it shows in all of his film work. Florey's other exceptional foray into television terror came on February 26, 1962 when he directed the second season episode of Boris Karloff's Thriller titled "The Incredible Doktor Markesan," which featured Karloff in the grisly title role. It is considered among the finest episodes of that series.

An exceptional contributor to the episode is George T. Clemens, the remarkably talented cinematographer for this episode as well as the majority of the episodes in the show's run. Clemens was awarded an Emmy for his work on the series. "Perchance to Dream" must have offered its own particular challenges as the episode takes place mostly within a dream context and had to be conveyed, often by subjective camera, as a frighteningly unstable environment. The dream sequences at the amusement park are, quite simply, some of the finest sequences in the entire series.

"Perchance to Dream" is an episode that bears re-watching every so often for it has a unique ability to refresh itself with each new viewing and frequently lends itself to new insights and new interpretations. It is one of what can be considered Beaumont's Dream Trilogy, which, along with the second season episode "Shadow Play" and the third season episode "Person or Persons Unknown," explores the various dramatic possibilities of dreams and nightmares, which were recurrent thematic concerns for Beaumont.

High points of the episode include the roller coaster sequence, a dizzying and terror-filled moment highlighted by Maya's frantic laugh track, the clashing juxtaposition of the roller coaster to the surrealist background, and Van Cleave's jarring and otherworldly music, which paints the entire scene a hallucinatory hue which thoroughly disorients the viewer. When viewing the episode again, notice that when Hall first enters Rathmann's office and Rathmann helps him to lie down, the camera focuses in close on Hall's face; his eyes are closed. The lighting gradually diminishes and the music filters out to a fading quiet until all is nearly darkness and silence. Then, suddenly, the music swells and the lighting blooms brightly and Hall jumps up from the couch. Knowing the ending of the episode, one presumes that the moment the lights and music go down is the moment in which Hall has, in reality, died. It is this moment we come back to at the end. As Beaumont himself observed, Florey managed to subtly reveal a lot of sub-textual shading and symbolism in the script.

Perhaps the most important aspect which Beaumont brought to the series was a penchant for psychological horror stories which explored the darker aspects of the human mind and the subjectivity of a character's perceived reality. "Perchance to Dream" is one of the finest examples of Beaumont's unique imaginative process.

Grade: B

Grateful acknowledgement to:

-The Fiend in You, edited by Charles Beaumont (Ballantine, 1962).

-"The Seeing I" by Charles Beaumont, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, December, 1959.

|

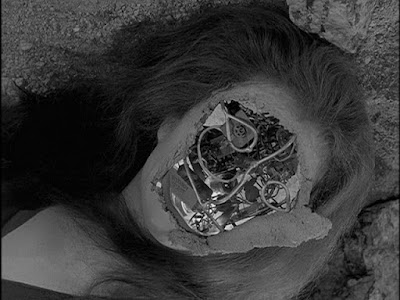

| Carl Koch's illustration for the story's original appearance in the Oct, 1958 Playboy |

Notes:

-Beaumont's original short story can be found in the October, 1958 issue of Playboy magazine, in the author's collections Night Ride and Other Journeys (Bantam, 1960) and The Magic Man (Fawcett, 1965), as well as in the retrospective volume Charles Beaumont: Selected Stories (Dark Harvest, 1988; paperback: The Howling Man (Tor, 1992)) and Twilight Zone: the Original Stories (edited by Greenberg, Matheson, & Waugh, MJF, 1985).

-John Larch also appeared in season two's "Dust" and season three's "It's a Good Life".

-Notice that the line "We've been expecting you, Mr. Hall" is spoken by Miss Thomas, Dr. Rathmann's receptionist, at the beginning of the episode and is also later spoken by Maya within Hall's dream while they are going through the funhouse at the amusement park, cluing us in on her dual role in the episode.

-Robert Florey also directed season one's "The Fever" and season five's "The Long Morrow."

-Writer William F. Nolan, a close friend of Charles Beaumont, has related the story of Beaumont's innate fear of amusement parks and, in particular, roller coasters. The story goes that the two writers, on a whim, entered an amusement park funhouse late one evening. Once inside the dark and disorienting structure, Beaumont began to convince Nolan that the ticket taker, a rough-looking young man in a leather jacket, had followed them in with the intention of killing them both with a switchblade knife Beaumont claims to have seen the young man brandishing at the ticket booth. Working themselves into an imaginative frenzy, they rushed through the funhouse only to discover that the young ticket taker had not moved from where they had last seen him. These experiences were not, according to Nolan, uncommon for Beaumont or those in his company, for the writer often allowed his imagination to get carried away, much like Edward Hall in "Perchance to Dream."

-"Perchance to Dream" was adapted as a Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring Fred Willard.

-Notice that the line "We've been expecting you, Mr. Hall" is spoken by Miss Thomas, Dr. Rathmann's receptionist, at the beginning of the episode and is also later spoken by Maya within Hall's dream while they are going through the funhouse at the amusement park, cluing us in on her dual role in the episode.

-Robert Florey also directed season one's "The Fever" and season five's "The Long Morrow."

-Writer William F. Nolan, a close friend of Charles Beaumont, has related the story of Beaumont's innate fear of amusement parks and, in particular, roller coasters. The story goes that the two writers, on a whim, entered an amusement park funhouse late one evening. Once inside the dark and disorienting structure, Beaumont began to convince Nolan that the ticket taker, a rough-looking young man in a leather jacket, had followed them in with the intention of killing them both with a switchblade knife Beaumont claims to have seen the young man brandishing at the ticket booth. Working themselves into an imaginative frenzy, they rushed through the funhouse only to discover that the young ticket taker had not moved from where they had last seen him. These experiences were not, according to Nolan, uncommon for Beaumont or those in his company, for the writer often allowed his imagination to get carried away, much like Edward Hall in "Perchance to Dream."

-"Perchance to Dream" was adapted as a Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring Fred Willard.

-JP