In

which we take a closer look at each issue of the magazine. For our capsule

history of the magazine, go here.

Volume

1, number 11 (February, 1982)

Cover

art: John Oberdorf

TZ Publications Inc.

President

& Chairman: S. Edward Orenstein

Secretary/Treasurer:

Sidney Z. Gellman

Executive

Vice-Presidents: Leon Garry, Eric

Protter

Executive

Publisher: S. Edward Orenstein

Publisher:

Leon Garry

Associate

Publisher and Consulting Editor: Carol

Serling

Editorial

Director: Eric Protter

Editor:

T.E.D. Klein

Managing

Editor: Jane Bayer

Assistant

Editors: Steven Schwartz, Robert

Sabat

Contributing

Editors: Gahan Wilson, Robert

Sheckley

Design

Director: Derek Burton

Art

and Studio Production: Georg the Design

Group

Production

Director: Edward Ernest

Controller:

Thomas Schiff

Administrative

Asst.: Doreen Carrigan

Public

Relations Manager: Jeffrey Nickora

Accounting

Mgr.: Chris Grossman

Circulation

Director: William D. Smith

Circulation

Manager: Janice Graham

Eastern

Circulation Manager: Hank Rosen

Western

Newsstand Consultant: Harry Sommer

Advertising

Manager: Rachel Britapaja

Adv.

Production Manager: Marina Despotakis

Advertising

Representatives: Barney O’Hara &

Associates, Inc.

Contents:

--In the Twilight Zone: “A word or two

of explanation . . .” by T.E.D. Klein

--Other Dimensions: Books by Robert

Sheckley

--Other Dimensions: Screen by Gahan

Wilson

--Other Dimensions: Music by Jack

Sullivan

--“Playing the Game” by Gardner Dozois

and Jack Dann

--“Essence of Charlotte” by Charles L.

Grant

--“Other” by Jor Jennings

--“My Old Man” by George Alec Effinger

--“The Other Train Phenomenon” by

Richard Bowker

--TZ Interview: Wes Craven by Tom

Seligson

--TZ Screen Preview: Swamp Thing by Jim

Verniere

--The Gargoyles of Gotham by Don

Hamerman and Stephen DiLauro

--“Holiday” by Richard Christian

Matheson

--“Top of the Stairs” by Stephen Schlich

--“The Voices of the Dead” by Leslie

Horvitz

--Show-by-Show Guide: TV’s Twilight

Zone, Part Eleven by Marc Scott Zicree

--TZ Classic Teleplay: “A Stop at

Willoughby” by Rod Serling

--Looking Ahead: In the March TZ

--In

the Twilight Zone: “A word or two of explanation . . .”

-Along

with the usual capsule biographies of the issue’s contributors is a lengthy

explanation by editor T.E.D. Klein for the inclusion of George Alec Effinger’s

story “My Old Man,” which Klein apparently felt was difficult or unusual enough

to warrant an explanation. After reading the story I found such a measure

unnecessary but nevertheless if the reader finds the tale confusing he/she can

consult this editorial space for enlightenment.

--Other

Dimensions: Books by Robert Sheckley

-Robert

Sheckley takes over book review duties following the departure of Theodore

Sturgeon. Sheckley previously appeared in the magazine with short stories in

the April, 1981, October, 1981, and January, 1982 issues. Sheckley’s

introduction explaining how difficult a time he had getting the column written

gives good indication of his comfort level with the job. Sheckley would appear

as the magazine’s book reviewer only two additional times before giving way to

Thomas M. Disch. Sheckley prefers to take a deeper look at a smaller number of

titles. Here is a small taste of what he had to say about the

four books he reviews.

Riddley Walker by Russell

Hoban:

“It’s

a fine book and the best science fiction novel to come along since Anthony

Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange.”

Program for a Puppet by Roland

Perry

“I

was two hundred pages into the thing before I decided I didn’t much like it,

and by then it was too late, I was hooked, so I finished it.”

Lovers Living, Lovers Dead by Richard

Lortz

“Lortz

puts his characters through changes increasingly strange, but believable and

compelling. The tone of the book is by turns dreamlike and businesslike as you

are led into mounting horror, ending at last with the big splatola.”

Bugs by Theodore Roszak

“The

novel attempts to marry science fiction and the occult – an important and

fruitful union, but not too convincingly handled here.”

--Other

Dimensions: Screen by Gahan Wilson

-Wilson

reviews Polyester (1981) directed by John Waters, and Strange

Behavior (1981) directed by Michael

Laughlin. Since both films are independent features made on very small budgets,

Wilson takes a broader look at some successful independent horror films, examining

what works in these films, what hampers these films, and what characteristics

are shared by successful examples of the type. Wilson’s reviews of the two

films are highly favorable. Typical of Wilson’s column there is a good amount

of autobiography weaved into the reviews.

--Other

Dimensions: Music by Jack Sullivan

-This

new column provides the first part of a comprehensive look at classical music pieces which contains macabre or fantastic elements. The writer is Jack Sullivan, a

freelance cultural critic well-known as the author of the 1978 volume Elegant Nightmares: The English Ghost Story from

LeFanu to Blackwood. Sullivan also edited

Lost Souls: A Collection of English Ghost Stories (1983) and The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986). His music column runs through the August,

1982 issue with an additional column in the May/June, 1983 issue. Sullivan also

provided the magazine with essays on L.P. Hartley, Shirley Jackson, and H.R. Wakefield

as part of “The Essential Writers” series.

-This

is simply a fantastic column and something this reader has always been

searching for. It provides a detailed history of macabre classical music and

then moves into specific selections from an array of composers, uncovering

well-known works as well as lesser-known selections. Sullivan also provides a

listing of the best recordings of the pieces he discusses. Here are the

selections from this first installment:

Symphonie Fantastique by Berlioz

“Requiem”

by Berlioz

Todtentanz for Piano and Orchestra by Franz Liszt

“Late

Piano Music” by Liszt

“Mephisto

Waltz” by Liszt

“Night

on Bald Mountain” by Mussorgsky

Pictures at an Exhibition by Mussorgsky

“Songs

and Dances of Death” by Mussorgsky

Prometheus: The Poem of Fire by Alexander Scriabin

Piano

Sonatas by Scriabin

Le Sacre du Printemps by Igor Stravinsky

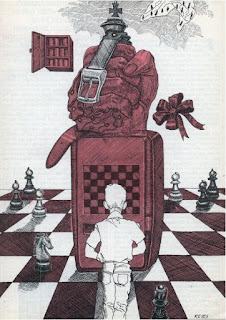

--“Playing

the Game” by Gardner Dozois and Jack Dann

Illustrated by E.T. Steadman

“The arena was inside his skull . . .

and as wide as the world”

-A

young boy sets in motion a series of reality altering events by playing a game

of mental concentration. Now he struggles to return his environment back to the

way it was before.

-Gardner

Dozois (1947-2018) began collaborating with Jack Dann (b. 1945) on dozens of

science fiction and fantasy anthologies beginning with Future Power in

1976. They began writing short stories together in 1981 and “Playing the Game”

was their third story collaboration. The story is a nifty speculative thriller

which leads the reader from ambiguity to shocking clarity in its closing lines.

It is an effective work from two legendary figures in the field of SF, both of

whom are best known as editors. Dozois edited Isaac Asimov’s Science

Fiction Magazine from 1986-2004, winning a

shelfful of awards for his editorship. Beginning in 1984 Dozois began compiling

The Year’s Best Science Fiction, a

series which saw its thirty-fifth volume published in 2018; sadly, this will be

the last such volume with Dozois’s selections. Dozois’s fiction has garnered

multiple awards and been collected across half a dozen volumes. Dann’s career

has likewise been very fruitful. Along with his work as editor he has published

novels, short stories, essays, reviews, and poems. Awards for his work include

the Nebula, World Fantasy, Ditmar, and Shirley Jackson Awards.

-“Playing

the Game” was included in the only annual volume of the magazine, Great Stories from Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone

Magazine (1982), as well as in The

1983 Annual World’s Best SF, edited by

Donald A. Wollheim and Arthur W. Saha. Both

authors included the story in individual collections, Dozois in Slow

Dancing Through Time (1990) and Dann in The

Fiction Factory (2005).

--“Essence

of Charlotte” by Charles L. Grant

Illustrated by Gregory Cannone

“One by one the townspeople died, as

silently and mysteriously as petals dropping from a rose.”

-A

man murders his mean-spirited, elderly aunt. Though he successfully disposes of

the body he discovers that Aunt Charlotte has returned from the grave in a

unique, and deadly, way.

-“Essence

of Charlotte” is an enjoyable tale of revenge from beyond the grave even if it

does not fully display the considerable talents of Charles L. Grant (1942-2006).

The stereotypical characters and surprising amount of humor in the story give

indication of Grant’s seriousness of intent (or lack thereof). Still, for those

who enjoy tales of ghostly vengeance it is a breezy and satisfying tale. The

story was reprinted in the first issue of Night Cry (with an illustration by D.W. Miller) but has never appeared

in one of Grant’s collections. The story plays on the theme of the deadly

plant, in this case roses, and would seem a logical choice to include in a

thematic anthology. Grant previously appeared in the magazine with an interview

of Stephen King for the first issue and a story, “Silver,” which I enjoyed,

from the July, 1981 issue.

--“Other”

by Jor Jennings

Illustrated by Randy Jones

“Return with us now to the great

American census of 1980 in a modern-day fairy tale about a literal-minded

census taker and a household that’s definitely . . .”

-A

harried wife and mother, who works as a census taker, finds herself in the home

of fairies who provide her with a different perspective on her life.

-This

story falls firmly in line with the sort of urban fantasy first popularized by

John W. Campbell’s Unknown magazine, in which an ordinary person

accidentally crosses over into Faery (or some equivalence). As such, it may be

of interest to fans of this story type but otherwise it largely falls flat. The

main character is the sort of hardworking wife/mother whose horrible husband

and horrible children have stolen her dreams which feels like too easy of a cliché

in modern fiction. The fairies only serve as grotesques with no real

differential between characters. The story is ultimately about transition, from

who you are to who you wish to be, yet the reader is not shown any of the

transitional effects of the main character’s encounter with the fairies.

Perhaps it is because Jennings’s own life is described in the issue’s editorial

as possessing “an easy-care husband (a lawyer) and a self-sufficient son (a

graduate student in physics)” that the fictional opposite presented in “Other” is

not successful.

-Arthur

W. Saha thought enough of “Other” to include it in The Year’s Best Fantasy Stories: 9 (1983). Jennings published only four SF

stories in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the last of which was “Tiger Hunt,” featured

in the inaugural volume of L. Ron Hubbard Presents: Writers of the Future (1985). Jennings died in 2015.

--“My

Old Man” by George Alec Effinger

Illustrated by José Reyes

“Seen through the eyes of memory, love

and hate have a way of being curiously interchangeable.”

-An

electronic game of chess magnifies a trouble man’s unpleasant memories of his

late father.

-As

stated before, this story apparently struck editor T.E.D. Klein as unusual or

difficult enough to warrant a lengthy explanation in the editorial column of

the issue. Although the story is heavily cloaked in figurative language, I

doubt it will cause any real problems for the mature reader. It is ultimately

about memory and childhood trauma centered on an abusive parent. Effinger (1947-2002)

uses an electronic game of chess to present a man forced to come to terms with

his dead father, terms which include the fact that the man still loves his

father despite his father’s abusive nature. It is a well-written and moving

piece which will appeal to fans of introspective fiction.

-The

story was reprinted in the Winter, 1985 issue of Night Cry with an

illustration by J.K. Potter (see end of post). It was collected in Effinger’s George Alan

Effinger Live! From Planet Earth (2005).

--“The

Other Train Phenomenon” by Richard Bowker

Illustrated by Robert Ray

“In which a lone researcher stumbles

upon the horrifying truth behind urban America’s version of the jelly-side-down

theory”

-A

subway rider on a broken-down train gets into a conversation with an eccentric

fellow passenger who has formulated a theory about the systematic ruination of

some people’s lives.

-“What

are the odds?” is the question this story humorously, and darkly, attempts to answer.

It seeks to find a solution to the reason why the misfortune heaped upon some

people defies the odds of probability. The story ultimately applies a light

touch with a humorous final scene in which the Men in Black come to remove the

man who knows too much. The story was reprinted in 100 Great Fantasy Short Short Stories (1984), edited by Martin H. Greenberg, Terry

Carr, and Isaac Asimov. Richard Bowker (b. 1950) is best-known for his The

Last P.I. series of novels, the first of

which, Dover Beach (1987), was

nominated for the Locus and Philip K. Dick Awards. After a lengthy break from

writing SF, Bowker returned in 2012 using e-publishing platforms to create new

works.

--TZ

Interview: Wes Craven by Tom Seligson

“Who’s made nightmares come true.”

-Despite

the subtitle of this interview with the well-known horror film director, it was

conducted before the film generally regarded as Craven’s masterwork, A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). Even so, Craven speaks at length on the ways in which dreams

and nightmares inform his early films. These early films, The Last House on

the Left, The Hills Have Eyes, and Deadly

Blessing, are discussed in detail as

Craven reveals the genesis, inspiration, and challenges in bringing each work

to the screen. Craven gives a detailed account of his improbable rise to the

director’s chair in the early portion of the interview. He discusses his

repressive upbringing in a staunchly religious household, his years as a

teacher, and his slow ascent up the filmmaking ranks performing technical jobs

on independent features. The final portion of the interview is dedicated to

Craven’s then-current production, Swamp Thing (1982), a feature adaptation of the DC Comics character.

-Craven's direct connection with The Twilight Zone is as a director of some of the best episodes of the Twilight Zone revival television series. Craven directed the premier episode, "Shatterday," based on the story by Harlan Ellison and starring Bruce Willis, as well as such well-regarded segments as Alan Brennert's "Her Pilgrim Soul" and George R.R. Martin's "The Road Less Travelled." Craven also directed the segments "Chameleon," "Word Play," and "Dealer's Choice."

-Craven's direct connection with The Twilight Zone is as a director of some of the best episodes of the Twilight Zone revival television series. Craven directed the premier episode, "Shatterday," based on the story by Harlan Ellison and starring Bruce Willis, as well as such well-regarded segments as Alan Brennert's "Her Pilgrim Soul" and George R.R. Martin's "The Road Less Travelled." Craven also directed the segments "Chameleon," "Word Play," and "Dealer's Choice."

-I

have been very impressed with the quality of the interviews featured in these

early issues. They benefit from being conducted by knowledgeable writers and

critics who are clearly genre fans. This interview with Craven is no exception.

It contains a wealth of information and inspiration for film fans and aspiring

filmmakers. Craven went on to direct such horror films as The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988), The People Under the Stairs (1991), and Scream (1996). He

died in 2015 at the age of 76.

--TZ

Screen Preview: Swamp Thing by Jim

Verniere

-The

magazine’s customary full-color film preview section is dedicated to looking at

the 1982 film Swamp Thing, written and directed by Wes Craven and

released by Embassy Pictures. It is an adaptation of the DC Comics character

created by writer Len Wein and artist Bernie Wrightson which first appeared in

the July, 1971 issue of DC’s horror anthology comic, The House of Secrets, before getting its own series for a short

run in the early 1970s. Craven’s film adaptation stars Adrienne Barbeau, Louis

Jourdan, and Ray Wise. Jim Verniere’s article gives a full account of the

making of the film, including perspectives from the director, producers,

principal performers, and technicians. The article takes a particular look at

the difficulties of filming on location in a South Carolina swamp and the

challenges endured by the crew, including special makeup artist Bill Munn, who

created the film’s practical effects.

-Although

Swamp Thing is not considered among Craven’s finest efforts, it continues to

possess the charming feel of a comic book come to life, with campy special

effects, extreme lighting, and over-the-top performances. The film was only a

moderate financial success but still managed to spawn a sequel, The Return

of the Swamp Thing (1989), directed by

Jim Wynorski, which eschewed the serious tone of Craven’s film. A more notable

byproduct of Craven’s film is The Saga of the Swamp Thing, DC’s second attempt at a Swamp Thing title. This second volume of the story

included a celebrated run by British writer Alan Moore and American artists

Stephen R. Bissette and John Totleben. This series, edited by Karen Berger, is

widely regarded as the beginning of DC’s celebrated Vertigo line of mature

comics.

--The

Gargoyles of Gotham by Stephen DiLauro (text) and Don Hamerman (photography)

“Hidden like endangered species amid the

steel-and-glass skyline, a menagerie of grand and grotesque creatures stare

inscrutably at modern-day New York”

-This

interesting photography feature, the magazine’s first, takes the reader on a

tour of New York City from the perspective of the jutting gargoyles which adorn

the city’s most renowned buildings. Stephen DiLauro approaches theories of the

origin of the gargoyle, their installation in the New World, and their

relevance to modern-day culture. The photography is the real draw here, of

course, and the grotesque gargoyles are a marvel to behold despite the limitations

of a black-and-white magazine.

--“Holiday”

by Richard Christian Matheson

Illustrated by Anna Rich

“One of the nicest things about

vacationing alone is that you meet the most unexpected people!”

-A

man vacationing alone meets an eccentric older gentlemen who turns out to be

Santa Claus.

-This

is on the lighter end of Matheson’s (b. 1953) fictional output. The son of Twilight Zone writer

Richard Matheson, and a highly successful television writer in his own right,

Matheson’s prose fiction tends toward the concision of the short-short: dark,

shocking, often experimental, tales written in terse, forceful language.

Although “Holiday” was collected in Matheson’s 1987 volume Scars, it differs markedly from the other stories

in that collection. It is a rather straight forward, humorous piece about a man

who meets Santa Claus on vacation. It has been reprinted in such themed

anthologies as The Magic of Christmas (1992)

and A Yuletide Universe (2003).

--“Top

of the Stairs” by Stephen Schlich

Illustrated by Frances Jetter

“It was just an old wooden staircase,

twenty-eight steps high – but it led to the upper reaches of Hell.”

-A

newly-disabled man is forced to reckon with a crime for which he was never punished,

until that punishment comes from beyond the grave.

-This

enjoyable horror story is thematically related to such better-known tales of

the type as Henry Slesar’s “The Jam” (1958) and William F. Nolan’s “The Party”

(1967). These stories center on a character who has hidden some essential

knowledge away from themselves only to discover too late the dire straits they

find themselves in. The final sequence of the story is effectively unnerving,

if a bit predictable. The story has not been reprinted since its appearance in

this issue.

-Stephen

Schlich published the occasional horror story in the genre magazines and

anthologies of the 1980s and 1990s. “Top of the Stairs” was the first of these

stories. The most recent, “Inside the Iron Maiden,” appeared in 2006 in editor

Christopher Conlon’s Poe’s

Lighthouse: New Collaborations with Edgar Allan Poe. The issue’s editorial column indicates that Schlich also published

mystery stories and worked for a time as a newspaper journalist.

--“The

Voices of the Dead” by Leslie Horvitz

Illustrated by Earl Killeen

“How could she have known, on that night

in the cemetery, that a message from beyond the grave would bring so strange an

answer from the living?”

-A

young actress becomes enamored with attempting to record the voices of the dead

until she learns the lengths to which the living were willing to go to connect

with a dead loved one.

-The

longest story in the issue, “The Voices of the Dead” is a character piece, with

the supernatural angle of the tale used as a tool to examine the interpersonal

relationships between the main character, the aloof and complicated man she

loves, and the dead woman who comes between them. It is a well-written story

with excellent characterization and a pleasantly creepy ending. Horvitz placed

a handful of stories in Charles L. Grant’s horror anthologies of the 1980s,

most notably in the Shadows series. He also published two horror novels,

The Dying and Blood Moon (both 1987), at the height of the horror

boom in paperback publishing.

--Show-by-Show

Guide: TV’s Twilight Zone: Part Eleven by Marc Scott Zicree

-Zicree,

author of The Twilight Zone Companion

(now in its 3rd edition),

continues his early examination of the series by providing the credits,

narrations, and summaries of these third season episodes: “The Little People,”

“Four O’Clock,” “The Trade-Ins,” “Hocus-Pocus and Frisby,” “The Dummy,” “The

Changing of the Guard,” “Young Man’s Fancy,” “I Sing the Body Electric,” and

“Cavender Is Coming.” We have reviewed these episodes as part of our third

season coverage and you can find our reviews under the episode titles in the

sidebar section titled Directory.

--TZ

Classic Teleplay: “A Stop at Willoughby” by Rod Serling

-The

complete shooting script of this fan-favorite episode is presented here

accompanied by production stills. “A Stop at Willoughby” was a first season

episode written by Rod Serling and directed by Robert Parrish. It starred James

Daly as a stressed-out advertising agent who longs to escape to the idealized

town of Willoughby. It originally aired on May 6, 1960. As frequent readers of

the blog may already be aware, our opinion of this episode diverges from the

prevailing opinion among viewers. Many TZ fans put this one near the top of the

series. We put it closer to the middle. If you are interested in our take on

the episode, you can find it here.

--Looking

Ahead: In March’s TZ

-Next

month looks like a great issue. Robert Sheckley reviews books by Peter Straub,

Cornell Woolrich, and Gahan Wilson, the latter of whom reviews the movie Time Bandits. Jack

Sullivan returns to continue his music column about macabre and fantastic

classical music. SF legend Fritz Leiber, one of this writer’s personal

favorites, is interviewed and Leiber’s 1947 tale, “The Man Who Never Grew

Young,” is reprinted with a new illustration by José Reyes. We have a story by

Barbara Owens, “The New Man,” which was later adapted for Tales from the

Darkside. We also look at stories by

Kevin Cook, Ron Goulart, Elizabeth Morton, Robert E. Vardeman, Larry Tritten,

Steve Rasnic Tem, and Richard Stooker. On the film front we have Ed Naha’s set

visit to John Carpenter’s The Thing and

a full-color preview of a Jack-the-Ripper thriller, Still of the Night. Finally, Marc Scott Zicree jumps into the

fourth season of his episode guide and Rod Serling’s teleplay for his moving

first season episode, “A Passage for Trumpet,” is presented. We will get to all

of that in our next installment. See you then!

|

| D.W. Miller's illustration for Charles L. Grant's "Essence of Charlotte" TZ Magazine Special: Night Cry (1984) |