|

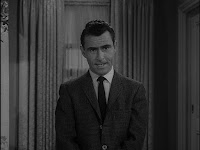

| Pictured here: David Gurney (Richard Long) on a trip to the Twilight Zone |

“Person or Persons Unknown”

Season Three, Episode 92

Original Air Date: March 23, 1962

Cast:

David Andrew Gurney: Richard Long

Dr. Koslenko: Frank

Silvera

Wilma #1: Shirley

Ballard

Wilma #2: Julie

Van Zandt

Sam Baker: Ed

Glover

Clerk: Betty

Harford

Policeman: Michael

Keep

Bank Guard: Joe

Higgins

Mr. Cooper: John

Newton

Sam the Bartender: Clegg Hoyt

Truck Owner: Bob

McCord

Crew:

Writer: Charles

Beaumont (original teleplay)

Director: John

Brahm

Producer: Buck

Houghton

Production Manager: Ralph W. Nelson

Director of Photography: Robert W. Pittack

Art Direction: George

W. Davis and Merrill Pye

Set Decoration: Keogh

Gleason

Assistant Director: E. Darrell Hallenbeck

Casting: Robert

Walker

Film Editor: Bill

Mosher

Sound: Franklin

Milton and Bill Edmondson

Music: Stock

And Now, Mr. Serling:

“Next week we again borrow from the considerable

talents of Charles Beaumont and we take a fast trot on the wild side. Picture

if you will, a man who wakes up in a strange world, knows everyone, knows every

place, feels very much at home. The strangeness comes from the fact that no one

knows him. Try this one for size on the next Twilight Zone. It’s called ‘Person

or Persons Unknown.’

“Habit is something you do when pleasure is gone, and

certainly this is not the way to smoke. I prefer to smoke Chesterfields and get

the rich taste of 21 great tobaccos. Blended mild not filtered mild. Smoke for

pleasure. Smoke Chesterfields.”

Rod Serling’s Opening Narration:

“Cameo of a man who has just lost his most valuable

possession. He doesn’t know about the loss yet. In fact, he doesn’t even know

about the possession. Because, like most people, David Gurney has never really

thought about the matter of his identity. But he’s going to be thinking a great

deal about it from now on, because that is what he’s lost. And his search for

it is going to take him into the darkest corners…of the Twilight Zone.”

Summary:

David Gurney wakes up in his home after a long night of

revelry. His wife Wilma is asleep next to him. After realizing he is late for

work he attempts to make himself presentable all the while talking to his

sleeping wife. He is regretting the late night and is apparently losing the

fight with his hangover.

When Wilma finally awakens she screams. She looks at

Gurney as if he is a total stranger. Believing her behavior to be an act he

informs her that he is late for work. She says she has never seen him before in

her life. More irritated than shocked, Gurney leaves for work.

At the bank where he works, Gurney notices a man he does

not recognize sitting in his desk. Still believing the strange morning to be

part of an elaborate gag, he asks the man with mocking politeness to give him

back his desk. The stranger looks at him with a bemused face and does not

attempt to move. Gurney tries getting the attention of his co-workers but they

all seem to look at him with the same confused expression. Frustrated, he

begins to yell at the stranger, demanding that he get up. A security guard

escorts him outside where he sees Wilma standing in front of a police cruiser.

She identifies Gurney as the man who broke into her apartment earlier that

morning. After a fruitless argument, officers arrest Gurney.

Later, Gurney finds himself in a psychiatric hospital

trying to prove his sanity. A doctor named Koslenko tells him that he has

created a fantasy life in order to escape his problems. Gurney says he can

prove his story and asks for a phone to call his mother. She claims that she does not have a son named David Gurney. He reluctantly gives the phone back to the

doctor. He still believes that he can make sense of the situation and prove his

innocence. He crashes through a window and takes off running.

He arrives at a bar, a secret place that he has never

mentioned to anyone. Not surprisingly, the bartender fails to recognize him.

Gurney can feel his sanity slipping. Then he gets an idea. He races to a photography

studio to pick up a photograph of himself and his wife at the zoo. His wife, he

says, does not know that the photograph exists. The counter clerk hands him the

photograph and he is relieved when he sees his wife in the picture with his arm

around her. As he opens the door to leave he is greeted by Dr. Koslenko and

several police officers. Gurney hands the doctor the photograph but the

doctor’s face remains expressionless. Gurney snatches the picture out of his

hands and looks at it. In the photograph David Gurney stands alone, his arm

around no one. He collapses to the ground, sobbing.

Moments later, he wakes up in his apartment. It was just

a dream, he realizes, a nightmare. He begins talking to his wife who is in the

bathroom. He tells her about his terrifying dream and his hangover. Wilma walks

into the bedroom. Gurney stares at her in disbelief. This is not his wife. He

has never seen this woman before in his life. Finally fearing that his sanity

may have officially left him, he collapses on the bed in horror.

Rod Serling’s Closing Narration:

“A case of mistaken identity or a nightmare turned

inside out? A simple loss of memory or the end of the world? David Gurney may

never find the answer, but you can be sure he’s looking for it…in the Twilight

Zone.”

Commentary:

“Person

or Persons Unknown,” Charles Beaumont’s twenty-four minute urban nightmare

about mistaken identity, could be considered the quintessential Twilight Zone episode for its premise illustrates the theme present in the majority of the show’s

darker efforts: a person inexplicably faced with a situation beyond their

comprehension inducing a terror that they cannot share with anyone else. Rod

Serling often described the most devastating type of fear as a fear of the

unknown that affects only one person, a fear which that person cannot share

with anyone else. Richard Matheson described the thematic element running

throughout the majority of his work in a similar manner: “an individual

isolated in a threatening world, attempting to survive.” If the main focus of

the show was to explore this particular part of human psychology then it makes

sense that its three main contributors would all have a substantial interest in

the same area. The way they approached the subject, however, was unique to each

writer.

Serling

often approached the theme in a very humanistic manner, where a character’s

fate is determined by their own moral compass. The good guys are rewarded with

a happy ending and the bad guys usually suffer a less appealing fate. Matheson was

fascinated with social interaction and exposing the affectations people wear

around others by placing his characters in unfamiliar situations. His stories

usually focus on how people react to their surroundings. Beaumont possessed an

unquestionable fascination with human psychology, particularly in how our

subconscious influences our personality and our interpretation of the world

around us.

The

plot of this episode bears a strong resemblance to Serling’s “And When the Sky

Was Open,” which is a loose adaptation of Richard Matheson’s story

“Disappearing Act,” and Matheson’s own “A World of Difference.” The basic

premise of “Person or Persons Unknown” actually feels more like a Matheson

idea than a Beaumont idea. The most terrifying thing about this story is that

at no time does it attempt to explain what is happening or why. So the audience

knows exactly what David Gurney knows and they experience the same sense of absurd

bewilderment that he is experiencing. Why has this happened? Who or what is

causing it to happen? Is Gurney insane or is he in an alternate reality of some

kind? Beaumont never tells us. Matheson excelled at this type of story.

Beaumont

brought his personality to the story by having a psychiatrist provide a

possible explanation for Gurney’s predicament. Depressed or unhappy with his

own life, our hero has manufactured a fictional character named David Gurney

and given him a happy, normal life to substitute for his own. Beaumont often

used psychiatrists as a way of probing a character’s subconscious. “Perchance

to Dream,” “Miniature,” and “Number Twelve Looks Just Like You”—in which Long

coincidentally plays an absurdly flamboyant psychiatrist named Sigmund

Friend—all feature doctors of the mind in varying degrees of authority.

Beaumont

also had a life-long obsession with dreams and how they represent our

personality. In an interview with the San

Diego Union Beaumont said that as a child he would dream episodically, with

a different episode each night. He examined this in his very first teleplay for

the show, “Perchance to Dream,” where protagonist Edward Hall is experiencing a

reoccurring nightmare which inches along each time he falls asleep, eventually

ending with his death, both in the dream and in real life. This is the first of

a trilogy of episodes written by Beaumont which explore the process of dreaming,

the second being his season two episode “Shadow Play” and the third being

“Person to Persons Unknown.” All three episodes explore basically the same

theme, although in the latter two the characters and images change from one

dream to another, but the fear is always the same: the hero is trapped in a

nightmare which he cannot escape. Beaumont ends “Persons to Persons Unknown” by

letting the audience briefly think that they have arrived at an explanation

only to leave them, and David Gurney, back where they began. He awakens from a

nightmare into a nightmare.

No

matter the device he used to explore it, Beaumont seemed to be endlessly

fascinated with the subconscious mind for this theme occurs again and again

throughout his work. His story “The Hunger” is about sexual repression. “Fair

Lady” explores repressed loneliness. “In His Image” explores the process of

rediscovering forgotten memories—even though they turn out to be someone else’s

memories. Beaumont had an immense interest in the make-up of the human mind.

Had his life not been cut tragically short he likely would have produced a

novel-length work on the subject.

“Person

or Persons Unknown” has one of the most clever twist endings in the show’s

history (it was number 18 on our 20 best twist endings countdown). It is also

one of the most subtle which, unfortunately, may diminish its shock value upon

a first viewing. The main reason it is lost on many viewers is that the first

Wilma doesn’t have much screen time. By the time the audience is introduced to

Wilma #2, the original Wilma hasn’t been on screen for almost fifteen minutes.

And for much of her screen time she is wearing a head wrap so the dramatic

switch in hair color, which is the main visual indicator that it is a different

actress, does not pack the punch that it should. It is a brilliant idea on

paper but one that slightly loses its impact on the screen.

This

is likely due to the somewhat lackluster direction from Twilight Zone stalwart John Brahm. This is atypical direction for

Brahm whose signature dark, dream-like style, evident in episodes like

“Judgement Night” and “Shadow Play,” is a perfect fit for the show. Instead of

focusing on the dream aspect of this story Brahm takes a more realistic

approach to what is happening. Instead of shadows and dark imagery, the entire

episode takes place in the middle of the day with many exterior scenes under

bright burning sunlight. This cheats the episode of the moody atmosphere needed

in this type of story. Brahm does make interesting use of close head shots of Richard

Long, showcasing his animated facial expressions.

Long

is without a doubt the best thing about this episode. He gives David Gurney a

slightly off-putting personality which actually helps to make him a more

relatable character. Instead of losing his mind due to having his life pulled

out from under him he remains defiant and rational until the end. As mentioned,

Long appears in Beaumont and John Tomerlin’s fifth season episode “Number

Twelve Looks Just Like You” where he plays several different characters. Long

started acting while still in his teens, first appearing in the film Tomorrow is Forever with Orson Welles

and Claudette Colbert in 1946 and then in Welles’s The Stranger that same year. He also appeared in four of the Ma and

Pa Kettle films. As an adult he appeared in several memorable horror films

including William Castle's House on Haunted Hill (1959).

He is probably best remembered for his roles in Bourbon Street Beat, 77 Sunset

Strip, and The Big Valley. He

also appeared in episodes of Alfred

Hitchcock Presents and The Alfred

Hitchcock Hour. In 1974 he suffered several heart attacks within weeks of

each other and died at the age of 47.

While it has its share of flaws “Person or Persons

Unknown” is still an enjoyable episode. Beaumont’s script is solid and Long’s

performance is immensely entertaining to watch. It’s an episode which strips

the show’s thematic thread to its rawest form and illustrates what it strove to say about fear and the human condition, that man’s greatest

and oldest fear is simply being alone.

Grade: B

Grateful acknowledgement to:

--The Twilight Zone Scripts of Charles Beaumont, Volume One, edited by Roger Anker (Gauntlet Press,

2004)

--Richard Matheson: Collected Stories edited by Stanley Wiater (Dream

Press, 1989)

--The Twilight Zone Definitive Edition DVD Season One (Image Entertainment, 2004)

--Original Pilot Version of

“Where Is Everybody?”

--Rod Serling 1975 Lecture at Sherwood Oaks College

Notes:

--Richard Long also appears in the season five episode

“Number Twelve Looks Just Like You” co-written by Beaumont and John Tomerlin.

--John Brahm directed twelve episodes of The Twilight Zone,

more than anyone else—Douglas Heyes and Buzz Kulik are tied for second place

with nine episodes each. He is also the only director to contribute to all five

seasons of the show. His credits include season one’s “Judgement Night,”

“Mirror Image,” and “The Four of Us Are Dying,” season two’s “Shadow Play” and

season four’s “The New Exhibit.”

--This is the first of twenty episodes for director of

photography Robert W. Pittack. His other contributions to the show include the

classics “Death Ship,” “Jess-Belle,” “Miniature,” “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,”

and “Living Doll.”

--Listen to the Twilight Zone Radio Drama starring

John Schneider.

--Brian