|

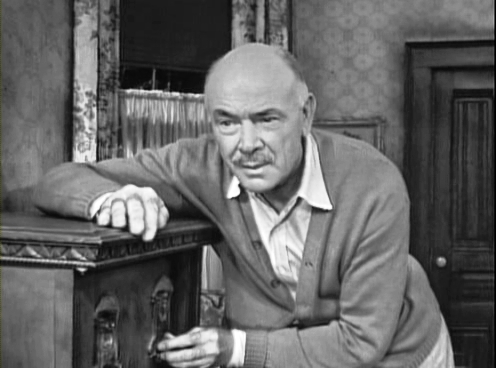

| Ed Lindsay (actor Dean Jagger) tunes in to the Twilight Zone |

"Static"

Season Two, Episode 56

Original Air Date: March 10, 1961

Cast:

Ed Lindsay: Dean Jagger

Vinnie Broun: Carmen Matthews

Professor Ackerman: Robert Emhardt

Roscoe Bragg: Arch Johnson

Mrs. Nielsen: Alice Pierce

Miss Meredith: Lillian O'Malley

Mr. Llewellyn: J. Pat O'Malley

Boy: Stephen Talbot

Junk Dealer: Clegg Holt

Rock & Roll Singer: Jerry Fuller

Real Estate Pitchman: Eddie Marr

Girl in Commercial: Diane Strom

Disc Jockey (voice): Bob Crane

TV/Radio Announcer: Roy Bowan

Man #1: Bob Duggan

Man #2: Jay Overholts

Crew:

Original Air Date: March 10, 1961

Cast:

Ed Lindsay: Dean Jagger

Vinnie Broun: Carmen Matthews

Professor Ackerman: Robert Emhardt

Roscoe Bragg: Arch Johnson

Mrs. Nielsen: Alice Pierce

Miss Meredith: Lillian O'Malley

Mr. Llewellyn: J. Pat O'Malley

Boy: Stephen Talbot

Junk Dealer: Clegg Holt

Rock & Roll Singer: Jerry Fuller

Real Estate Pitchman: Eddie Marr

Girl in Commercial: Diane Strom

Disc Jockey (voice): Bob Crane

TV/Radio Announcer: Roy Bowan

Man #1: Bob Duggan

Man #2: Jay Overholts

Crew:

Writer: Charles Beaumont (based

on an unpublished story by OCee Ritch)

Director: Buzz Kulik

Producer: Buck Houghton

Associate Producer: Del Reisman

Art Direction: Robert Tyler Lee

Set Decoration: Buck Henshaw

Technical Director: Jim Brady

Assoc. Director: James Clark

Casting: Ethel Winant

Music: Stock

Associate Producer: Del Reisman

Art Direction: Robert Tyler Lee

Set Decoration: Buck Henshaw

Technical Director: Jim Brady

Assoc. Director: James Clark

Casting: Ethel Winant

Music: Stock

And Now, Mr.

Serling:

"Item of

consequence: a radio. A carryover from that other era when quiz shows went up

to only sixty-four dollars and entertainment was aimed only at the ears. Mr.

Charles Beaumont has given us a most unusual story called 'Static.' We invite

you to watch Mr. Dean Jagger fiddle with a few of these knobs, change a few

stations, and find a couple of programs that are broadcast only in The Twilight

Zone."

Rod Serling's

Opening Narration:

"No one ever

saw one quite like that because that's a very special sort of radio. In its

day, circa 1935, its type was one of the most elegant consoles on the market.

Now, with its fabric-covered speakers, its peculiar yellow dial, its serrated

knobs, it looks quaint and a little strange. Mr. Ed Lindsay is going to find

out how strange very soon, when he tunes in to the Twilight Zone."

Summary:

Ed Lindsay, an

elderly bachelor, lives in a boarding house in which the other tenants, also

elderly, spend their waning days and nights parked on couches and chairs taking

in endless hours of television. Lindsay, bored with this routine, goes down

into the basement of the boarding house and retrieves his old radio, a hulking

set that is over twenty five years old. He brings the radio up to his room and,

to his astonishment and delight, is able to catch many of the old radio

programs he remembers from his younger years, programs which have long since

gone off the air. When he tells the other tenants, they scoff at the idea. Most

frustrating for Ed is that he is only able to hear the old radio shows when he

is alone and is unable to prove to anyone else in the house that his old radio

is working some sort of magic.

Vinnie Broun is an elderly maid that

was once engaged to marry Ed many years ago. Circumstances prevented the

marriage and thereafter Vinnie and Ed have been living tensely under the same

roof, having grown into tired, bickering adversaries. Vinnie thinks Ed is

imagining the broadcasts of all those old radio shows and tells him in a frank

confession that she believes it is a result of them missing out on their one

chance at happiness all those years ago. Ed dismisses the idea the he is

imagining the broadcasts.

In an effort to stop Ed's descent

into what she believes to be an unhealthy fixation, Vinnie sells Ed's radio to

a junk dealer. When he finds out, Ed is furious and immediately retrieves his

radio, having to buy his own property back from the junk dealer. Fearing the

radio won't work the way it did before, Ed lugs it home and fires it up. It

still works and even better than before. When Ed calls Vinnie up to hear the

old broadcasts it is a young, vibrant version of Vinnie that appears in his

doorway. Ed, now a young man again, realizes that they’ve gone back in time to

be given a second chance.

Rod Serling's

Closing Narration:

"Around and

around she goes and where she stops nobody knows. All Ed Lindsay knows is that

he desperately wanted a second chance and finally got it, through a strange and

wonderful time machine called a radio, in the Twlight Zone."

Commentary:

In an interview with Buzz Kulik,

director of "Static," author Marc Scott Zicree (The Twilight Zone

Companion) suggests that "Static" is an episode which presents a theme opposite from that explored in the earlier episode "The Trouble with Templeton." Whereas "The Trouble with Templeton" says you can't

go back again (as does a bevy of episodes from "Walking Distance" to "The Incredible World of Horace Ford"), "Static" shows that, with a little magic, and a lot of

hope, you definitely can go back. A more apt comparison is perhaps the highly regarded third season episode "Kick the Can," scripted by close friend of and frequent collaborator with Charles Beaumont, writer George Clayton Johnson. In that episode, the children's game of kick-the-can transforms the aged in a nursing home back into their younger selves. "Static" displays the quintessential Twilight

Zone set up, the intrusion of a magical or fantastic element, in a highly

realistic setting. In other words, ordinary people caught up in extraordinary circumstances. It is interesting to note here, and it has been noted before

in other studies of the show, that the main writers of the show were all young men

in their early to mid 30s and yet returned time and again to create episodes

dealing with the elderly, exploring what it means to grow old with astonishing

insight into the regret and sorrow and, ultimately, hope that accompanies the aging process.

"Static" shares a lot of thematic ground with other Zone episodes

that center on elderly characters, such as the aforementioned "Kick the Can,"

"Nothing in the Dark," "The Hunt," “The Trade-Ins,” and "Night Call,"

among others; each being an example from the core writers of the show.

"Static" began as an unpublished short

story with the evocative title "Tune in Yesterday" by OCee Ritch, a friend of and frequent collaborator with Twilight

Zone writer Charles Beaumont. Ritch contributed to Beaumont's book on motor racing, The Omnibus of Speed: An Introduction to the World of Motor Sport, edited with William F. Nolan (G.P. Putnam's, 1958; "The Golden Days of Gilmore") and collaborated with Beaumont on nostalgic essays for Playboy and other magazines (published under Beaumont's name alone and later collected in Beaumont's volume, Remember, Remember? (Macmillan, 1963)). The two writers also collaborated on television scripts beyond their two efforts for The Twilight Zone, with "The Long Silence" for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (with William D. Gordon and based on "Composition for Four Hands" by Hilda Lawrence) as well as a teleplay for Boris Karloff's Thriller, "Guillotine," based on a story by Cornell Woolrich. A final collaboration was "Gate to Nowhere" for the dramatic series Channing. Ritch's name does not appear in the credits for any of these efforts. In 1962, Ritch had a small role in director Roger Corman's adaptation of Beaumont's 1959 novel, The Intruder, starring William Shatner. Other Beaumont friends William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson also appear in the film. Ritch wrote an article on making the film for the December, 1961 issue of Rogue magazine (under the simple title "The Intruder").

Ritch and Beaumont initially bonded over their shared love of automobiles (Ritch published several motorcycle repair manuals for the Chilton series in the 1960's) and discovered a shared passion for fantasy and nostalgia. Beaumont so liked the original title of "Static" that he re-titled his nostalgic essay on radio, originally published as "Requiem for Radio" in Playboy, as "Tune in Yesterday" for its appearance in Remember, Remember?

As recorded in Marc Scott Zicree's The Twilight Zone Companion, OCee Ritch got the idea for "Static" while attending a party thrown by writer Richard Matheson, also a frequent contributor to The Twilight Zone. At the party was an old time radio fan who performed bits from some of the old shows. Ritch struck upon the idea of being able to simply tune in to those old radio shows that were no longer on the air and set out to write a fantasy story around the concept. Instead of submitting "Tune in Yesterday" as a short story to a fiction magazine, Charles Beaumont convinced Ritch to submit the story for production on The Twilight Zone. Producer Buck Houghton accepted the story upon Beaumont's recommendation as well as on the condition that Beaumont wrote the teleplay adaptation. During the first two seasons, Houghton was particularly wary to let other writers in on the show. See his relationship with George Clayton Johnson for instance. Johnson had been selling stories to the series since the first season but had to bargain his way in to writing original teleplays for the show.

Ritch and Beaumont initially bonded over their shared love of automobiles (Ritch published several motorcycle repair manuals for the Chilton series in the 1960's) and discovered a shared passion for fantasy and nostalgia. Beaumont so liked the original title of "Static" that he re-titled his nostalgic essay on radio, originally published as "Requiem for Radio" in Playboy, as "Tune in Yesterday" for its appearance in Remember, Remember?

As recorded in Marc Scott Zicree's The Twilight Zone Companion, OCee Ritch got the idea for "Static" while attending a party thrown by writer Richard Matheson, also a frequent contributor to The Twilight Zone. At the party was an old time radio fan who performed bits from some of the old shows. Ritch struck upon the idea of being able to simply tune in to those old radio shows that were no longer on the air and set out to write a fantasy story around the concept. Instead of submitting "Tune in Yesterday" as a short story to a fiction magazine, Charles Beaumont convinced Ritch to submit the story for production on The Twilight Zone. Producer Buck Houghton accepted the story upon Beaumont's recommendation as well as on the condition that Beaumont wrote the teleplay adaptation. During the first two seasons, Houghton was particularly wary to let other writers in on the show. See his relationship with George Clayton Johnson for instance. Johnson had been selling stories to the series since the first season but had to bargain his way in to writing original teleplays for the show.

Beaumont took the adaptation as an

opportunity to change Ritch's story to suit the show as well as Beaumont’s own

writing style. Whereas Ritch's main character was an unhappily married man

looking to escape into the past, Beaumont changed him to an unhappy bachelor

that wanted a second chance to correct past mistakes. Beaumont also allowed

changes that would take ironic shots at the television industry, the very

medium which supported the show. It was an industry in which Beaumont worked

and thrived but for which he held no love, made apparent in the later essay on

old time radio, "Requiem for Radio." Beaumont presents the tenants of

the boarding house as the dull slaves of routine, whiling away their days in

front of the television whereas the introduction of the radio in the episode

drives all the action, is the catalyst for heated conversation and startling

confession, and inspires excitement and laughter. The

commercials presented on television are absurd and humorous caricatures of the

type of advertising common to the 1960's. It is made clear that Beaumont felt

television an unfit successor to radio. As Ed Lindsay poignantly states in the

episode, radio is “a world that has to be believed to be seen.”

To create the genuine feel of old time

radio, the episode utilized recordings from old broadcasts (The F.D.R. fireside

chat and a segment from The Fred Allen Show) as well as creating new

recordings, including the use of a Los Angeles radio announcer named Bob Crane

who would later star on the popular television series Hogan's Heroes.

“Static” hinges so heavily upon a

single concept (the magic radio) that a good script and better performances

were necessary to keep the action moving smoothly along. Dean Jagger is perfectly cast as Beaumont’s unhappy

bachelor and manages to tamper his performance so as not to

alienated the viewer by simply playing a one-dimensional grump, but rather like

a man trapped in a miserable situation from which derives his ill tempered

behavior, particularly toward the character of Vinnie. Jagger portrays the loneliness

of a man surrounded by people that, for the most part, he cannot relate to and

it lends his character weight as a relatable, if not pitiable, figure. Jagger

was born in Ohio on November 7, 1903. After studying acting in Chicago, he

found character roles in films and later on television, eventually

winning a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award for Twelve O’Clock High (1949). Jagger’s other genre credits include

the films Revolt of the Zombies (1936),

X: the Unknown (1956) and Alligator (1980), and an episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. He died in

Santa Monica in 1991.

Ably supporting Jagger are Carmen

Matthews as Vinnie Broun and Robert Emhardt as Professor Ackerman. Matthews was

born in Philadelphia in 1914 and was trained in the theater. She found early television

work in anthology programs such as Kraft

Theater and Goodyear Playhouse and

continued working in television throughout her career, finding the occasional

film role. Her other genre credits include television episodes of Suspense (1952), 'Way Out, six episodes of Alfred

Hitchcock Presents, and an episode of Tales

from the Darkside. She died in 1995.

Actor Robert Emhardt amassed an astounding

number of credits in theater and television over his long career. He seemed tailored to play villains but found a variety of roles in every type of show

on the small screen, from soap operas to westerns to science fiction.

He was born in Indianapolis in 1914 and died in California in 1994. His other genre

credits include episodes of Alfred

Hitchcock Presents, Alcoa Presents: One Step Beyond, and the Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

“Static” remains a memorable episode

that is unfortunately given the videotape and stock music treatment and is thus

not as memorable as one of the better produced episodes. It is apparent

in certain aspects of production, however, that a lot of care was given to

making the episode a success. One of the show’s best writer was given the job

to adapt the source material and effort was made to replicate the authentic

sounds of old time radio. The only major flaw in the episode is the choice to

use older actors and attempt to make them look young again through color and

makeup processes for the surprise ending. The typical approach to

this type of fantasy is to use makeup to age younger actors (see this done effectively in "The Howling Man") and then

simply remove the makeup when the time comes to reveal the younger versions of

the characters. Often, two different sets of actors are used to achieve the

same effect. The makeup department isn’t quite able to convincingly turn back

the clock forty years on the two main characters but nevertheless the episode

remains effective, with a good script and solid acting all around.

The Twilight Zone was given the radio drama treatment beginning in 2002 with The Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, conceived, produced, and directed by Carl Amari, with episode adaptations by Dennis Etchison. Read our look at this radio series.

The Twilight Zone was given the radio drama treatment beginning in 2002 with The Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, conceived, produced, and directed by Carl Amari, with episode adaptations by Dennis Etchison. Read our look at this radio series.

Grade: B

Grateful acknowledgement is made to William F. Nolan for The Work of Charles Beaumont: An Annotated Bibliography and Guide (2nd edition, Borgo Press, 1990)

Note:

Note:

-“Static” was

adapted as a The Twilight Zone Radio

Drama starring Stan Freberg.

--Jordan Prejean